Wall Carving At Dendera Courtesy: Christopher Dunn

-

-

-

- Note - You can hear Chris Dunn's 1-1-99

remarkable interview with Jeff in our RealAudio Archives.

-

-

- Egypt. Land of the Pyramids and a vast

collection of evidence that, like a taciturn teenager, is begging for understanding.

Contrary to conventional thought, for decades there has been an undercurrent

of speculation that the pyramid builders were more advanced. The speculation

is well placed. When attempts have been made to build pyramids using the

theorized methods of the ancient Egyptians, they have fallen considerably

short. The great pyramid is 483 feet high and houses 70 ton pieces of granite

lifted to a level of 175 feet. Theorists have struggled with stones weighing

up to 2 tons to a height of a few feet. One wonders if these were attempts

to prove that primitive methods are capable of building the Egyptian pyramids

or the opposite? Executing this theory to practice has not revealed the

theory to be correct. Do we need to revise the theory, or will we continue

to educate our young with erroneous data?

-

- In August, 1984, I had an article published

in Analog magazine entitled "Advanced Machining in Ancient Egypt?"

It was a study of "Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh," the work of

Sir. William Flinders Petrie. Since the article's publication, I have been

fortunate to visit Egypt twice. With each visit I leave with more respect

for the industry of the ancient pyramid builders. An industry, by the way,

that does not exist today.

-

- While in Egypt in 1986, I visited the

Cairo museum and gave a copy of my article, along with a business card,

to the director of the museum. He thanked me kindly, threw it in a drawer

to join other sundry material, and turned away. Another Egyptologist led

me to the "tool room" to educate me in the methods of the ancient

masons by showing me a few cases that housed primitive copper tools.

-

- I asked my host about the cutting of

granite, for this was the focus of my article. He explained how they cut

a slot in the granite and inserted wooden wedges which they soaked with

water. The wood swelled creating pressure that split the rock. Splitting

rock is vastly different than machining it and this did not explain how

copper implements were able to cut granite, but he was so enthusiastic

with his dissertation, I did not wish to interrupt.

-

- To prove his argument, he walked me over

to a nearby travel agent encouraging me to buy airplane tickets to Aswan,

where, he said, the evidence is clear. I must, he said, see the quarry

marks there and the unfinished obelisk. Dutifully, I bought the tickets

and arrived at Aswan the next day. (After learning some of the Egyptian

customs, I got the impression that my Egyptologist friend had made that

trip to the travel agent many times.)

-

- The Aswan quarries were educational.

The obelisk weighs approximately 3,000 tons.

-

-

- Drill hole at the Aswan Quarries

-

- However, the quarry marks I saw there

did not satisfy me as being the only means by which the pyramid builders

quarried their rock. Located in the channel, which runs the length of the

obelisk, is a large round hole drilled into the bedrock hillside, measuring

approximately 12 inches in diameter and 3 feet deep. The hole was drilled

at an angle with the top intruding into the channel space. The ancients

may have used drills to remove material from the perimeter of the obelisk,

knocked out the webs between the holes and then removed the cusps.

-

- While strolling around the Giza Plateau

later in the week, I started to question the quarry marks at Aswan even

more. (I also questioned why the Egyptologist had deemed it necessary to

buy an airplane ticket to look at them.) I was to the South of the second

pyramid when I found an abundance of quarry marks of similar nature. The

granite casing stones which had sheathed the second pyramid were stripped

off and lying around the base in various stages of destruction. Typical

to all of the granite stones worked on were the same quarry marks that

I had seen at Aswan earlier in the week.

-

- This was puzzling to me. Disregarding

the impossibility of Egyptologists' theories on the ancient pyramid builders'

quarrying methods, are they really valid from a non-technical, logical

viewpoint? If these quarry marks distinctively identify the people who

created the pyramids, why would they engage in such a tremendous amount

of extremely difficult work only to destroy their work after having completed

it? It seems to me that these kinds of quarry marks were from a later period

of time and were created by people who were interested only in obtaining

granite, without caring from where they got it.

-

-

- Quarry marks at Aswan

-

- Archeology is largely the study of history's

toolmakers. It is with tools and artifacts created with tools, that we

come to understand a society's level of advancement. The hammer is probably

the first tool ever invented, and by hammer working metals, relatively

unsophisticated tools have forged some elegant and most beautiful artifacts.

Ever since man first learned that he could effect profound changes in his

environment by applying force with a reasonable degree of accuracy, the

development of tools has been a continuous and fascinating aspect of human

endeavor.

-

-

- Quarry marks on the Giza Plateau

-

- The Great Pyramid leads a long list of

artifacts that have been incredibly misunderstood and misinterpreted by

Egyptologists. They have postulated theories and methods based on a collection

of tools that are, at best, questionable. For the most part, primitive

tools that have been uncovered would be considered contempor-aneous with

the artifacts of the same period. This period in Egyptian history, however,

resulted in artifacts being produced in prolific number with no tools surviving

to explain their creation. The ancient Egyptians left artifacts behind

that are unexplainable in simple terms. The tools that have been uncovered

do not fully represent the "state-of-the-art" that is physically

evident in these artifacts. There are some intriguing objects surviving

this civilization which, despite its most visible and impressive monuments,

has left us with only a sketchy understanding of its full experience on

planet Earth.

-

- We would be hard pressed to produce many

of these artifacts today, even using our advanced methods of manufacturing.

The tools displayed as instruments for the creation of these incredible

artifacts are physically incapable of reproducing many of the artifacts

in question. Along with the enormous task of quarrying, cutting and erecting

the Great Pyramid and its neighbors, thousands of tons of hard igneous

rock, such as granite and diorite, were carved with extreme proficiency

and accuracy. After standing in awe before these engineering marvels and

then being shown a paltry collection of copper implements in the tool case

at the Cairo Museum, one comes away with a sense of frustration, futility

and wonder.

-

- The first British Egyptologist, Sir.

William Flinders Petrie, recognized that these tools were insufficient.

He admitted it in his book "Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh", and

expressed amazement regarding the methods the ancient Egyptians were using

to cut hard igneous rocks, crediting them with methods that "......we

are only now coming to understand." So why do modern Egyptologists

identify this work with a few primitive copper instruments?

-

- I am not an Egyptologist. I am a technologist.

I do not have much interest in who died when and whom they may have taken

with them, where they went to or when they may be coming back. No lack

of respect for the mountain of work and the millions of hours of study

conducted on this subject by highly intelligent scholars (professional

and amateur), but my interest, therefore my focus, is elsewhere. When I

look at an artifact with the view of how it was manufactured, I am unencumbered

with a predisposition to filter out possibilities because of historical

or chronological inequity. Having spent most of my career involved with

the machinery that actually creates artifacts of the modern kind, such

as jet-engine components, I am fairly well equipped to analyze and determine

the methods necessary for recreating an artifact under study. I have been

fortunate, also, to have training and experience in some non-conventional

methods of manufacturing, such as laser processing and electrical discharge

machining. That said, I should state that contrary to some popular speculations,

I have not seen the work of laser cutting on the Egyptian rocks. Still,

there is evidence of other non-conventional machining methods, along with

more sophisticated, conventional type sawing, lathe and milling practices.

-

- Undoubtedly, some of the artifacts that

Petrie was studying were produced using lathes. There is evidence, too,

in the Cairo Museum of clearly defined lathe tool marks on some "sarcophagi"

lids. The Cairo Museum contains enough evidence that, when properly analyzed,

will prove beyond all shadow of doubt that the ancient Egyptians used highly

sophisticated manufacturing methods. For generations the focus has centered

on the nature of the cutting tools that the ancient Egyptians used. While

in Egypt in February 1995, I uncovered evidence that clearly moves us beyond

that question to ask "what guided the cutting tool?"

-

- Although the ancient Egyptians are not

given credit for having a simple wheel, the evidence proves they had a

more sophisticated use for the wheel. The evidence of lathe work is markedly

distinct on some artifacts that are housed in the Cairo Museum and also

those that were studied by Petrie. Two pieces of diorite in Petrie's collection

were identified by him to be the result of true turning on a lathe.

-

-

- Creating Petrie's bowl shards.

-

- It is true that intricate objects can

be created without the aid of machinery, simply by rubbing the material

with an abrasive, such as sand, using a piece of bone or wood to apply

pressure. The relics Petrie was looking at, however, in his words "could

not be produced by any grinding or rubbing process which pressed on the

surface."

-

- To the inexperienced eye, the object

Petrie was studying would hardly be considered remarkable. It was a simple

bowl, made out of simple rock. Studying the bowl closely, however, Petrie

found that the spherical concave radius, forming the dish, had an unusual

feel to it. Closer examination revealed a sharp cusp where two radii intersected.

This indicates that the radii were cut on two separate axes of rotation.

-

- Having worked on lathes, I have witnessed

the same condition when a component has been removed from the lathe and

then worked on again without being recentered properly.

-

- On examining other pieces from Giza,

Petrie found another bowl shard which had the marks of true lathe-turning.

This time, though, instead of shifting the workpiece's axis of rotation,

a second radius was cut by shifting the pivot point of the tool. With this

radius they machined just short of the perimeter of the dish, leaving a

small lip. Again, a sharp cusp defined the intersection of the two radii.

-

- While browsing through the Cairo Museum,

I found evidence of lathe turning on a large scale. A sarcophagus lid had

distinctive marks of lathe turning.

-

-

- Sarcophagus Lid in the Cairo Museum

-

- The radius of the lid terminated with

a blend radius at shoulders on both ends. The tool marks near these corner

radii are the same as those I have witnessed when turning an object with

an intermittent cut. The tool is deflected under pressure from the cut.

It then relaxes when the section of cut is finished. When the workpiece

comes round again to the tool, the initial pressure causes the tool to

dig in. As the cut progresses, the amount of "dig in" is diminished.

-

- On the sarcophagus lid in the Cairo Museum,

tool marks indicating these conditions are exactly where one would expect

to find them!

-

- Petrie also studied the sawing methods

of the pyramid builders. He concluded that their saws must have been at

least 9 feet long. Again, there are indications of modern methods of sawing

on the artifacts Petrie was studying. The sarcophagus in the King's Chamber

inside the Great Pyramid has saw marks on the north end that are identical

to saw marks I have seen on granite surface plates.

-

- Today, these saw marks would reflect

either the differences in the aggregate dimensions of a wire band-saw with

the abrasive the wire entraps to do the cutting, or the side-to-side movement

of the wire or the wheels that drive the wire. The result of either of

these conditions is a series of slight grooves. The distance between the

grooves is determined by the feed-rate and either the distance between

the variation in diameter of the saw, or the diameter of the wheels. The

distance between the grooves on the coffer inside the King's Chamber is

approximately .050 inch.

-

- Egyptian artifacts representing tubular

drilling are the most clearly astounding and conclusive evidence yet presented

to identify the knowledge and technology existing in pre-history. The ancient

pyramid builders used a technique for drilling holes that is commonly known

as "trepanning." This technique leaves a central core and is

an efficient means of hole making. For holes that didn't go all the way

through the material, they reached a desired depth and then broke the core

out of the hole. It was not only evident in the holes that Petrie was studying,

but on the cores cast aside by the masons who had done the trepanning.

Regarding tool marks which left a spiral groove on a core taken out of

a hole drilled into a piece of granite, he wrote:

-

- "The spiral of the cut sinks .100

inch in the circumference of 6 inches, or 1 in 60, a rate of ploughing

out of the quartz and feldspar which is astonishing."

-

- After reading this, I had to agree with

Petrie. This was an incredible feed-rate for drilling into any material,

let alone granite. I was completely confounded as to how a drill could

achieve this feedrate. Petrie was so astounded by these artifacts that

he attempted to explain them at three different points in one chapter.

To an engineer in the 1880's, what Petrie was looking at was an anomaly.

The characteristics of the holes, the cores that came out of them, and

the tool marks indicated an impossibility. Three distinct characteristics

of the hole and core make the artifacts extremely remarkable. They are...

-

- 1. A taper on both the hole and the core.

-

- 2. A symmetrical helical groove following

these tapers which showed that the drill advanced into the granite at a

feed rate of .100 inch per revolution of the drill.

-

- 3. The confounding fact that the spiral

groove cut deeper through the quartz than through the softer feldspar.

In conventional machining the reverse would be the case.

-

- Mr. Donald Rahn of Rahn Granite Surface

Plate Co., Dayton, Ohio, told me, in 1983, that in drilling granite, diamond

drills, rotating at 900 revolutions per minute, penetrate at the rate of

1 inch in 5 minutes. This works out to be .0002 inch per revolution, meaning

that the ancient Egyptians were able to cut their granite with a feed rate

that was 500 times greater.

-

- The other characteristics create a problem.

They cut a tapered hole with a spiral groove that was cut deeper through

the harder constituent of the granite. If conventional machining methods

cannot answer just one of these problems, where do we look to answer all

three? I was just as puzzled as Petrie was when faced with this evidence.

When I finally found a solution to the problem, I could not wait to share

it. So I challenged some toolmakers I was working with who had used machine

tools and drills day in and day out for decades. All of them but one gave

up on the problem saying it could not be done. Each day I would ask this

one toolmaker if he had come up with a solution. Each day he said he was

still working on it. I offered, but he would not even take a hint! It was

a couple of weeks later before he came back to me and said, "You know

I think I have the answer to this problem. But it creates another problem....

They didn't have machinery like that back then!"

-

- He had independently analyzed the characteristics

of what Petrie was puzzling over and had come up with the same conclusion

as I had. We had both set out to find a method of manufacturing that would

explain all the characteristics found on these artifacts.

-

- I have discussed descriptions of several

artifacts having tool marks and characteristics that identified conventional

methods of machining. A sophisticated use of the lathe is clearly evident

on artifacts described by William Flinder Petrie in 1883, where radii were

being cut in diorite. A large sarcophagi lid in the Cairo Museum has distinct

tool marks which are common when turning objects with intermittent cuts

on a lathe. The question in my mind is out of what kind of materials were

their tools made?' In conventional machining the tool would need to be

hard enough to cut one of the hardest materials there is, yet tough enough

not to break under pressure. Their ability to make these cuts without the

rock splintering is astounding! (Note: For those who are locked into the

"official" chronology of the development of metals - copper doesn't

cut it. It is like saying that aluminum could be cut with butter.)

-

- What follows is a more feasible and logical

method and provides an answer to the question of techniques used by the

ancient Egyptians in all aspects of their work.

-

- The fact that the spiral is symmetrical

is quite remarkable considering the proposed method of cutting. The taper

indicates an increase in the cutting surface area of the drill as it cut

deeper, hence an increase in the resistance. A uniform feed under these

conditions, using manpower, would be impossible.

-

- Petrie theorized that a ton or two of

pressure was applied to a tubular drill consisting of bronze inset with

jewels. I disagree. This doesn't take into consideration that under several

thousand pounds pressure the jewels would undoubtedly work their way into

the softer substance, leaving the granite relatively unscathed after the

attack. Nor does this method explain the groove being deeper through the

quartz.

-

- The method I am about to propose, and

hope some of the readers have already figured out, explains how the holes

and cores found at Giza could have been cut. It is capable of creating

all the details that Petrie, myself and my colleague puzzled over. Unfortunately

for Petrie, the method was not known at the time he made his studies, so

it is not surprising that he could not find any satisfactory answers.

-

- The application of ultrasonic machining

is the only method that completely satisfies logic from a technical viewpoint,

and it explains all noted phenomena. Ultrasonic machining is the oscillatory

motion of a tool that chips away material, like a jackhammer chipping away

at a piece of concrete pavement, except much faster and not as measurable

in its reciprocation. The ultrasonic tool-bit, vibrating at 19,000 to 25,000

cycles per second (Hertz) has found unique application in the precision

machining of odd shaped holes in hard, brittle material such as hardened

steels, carbides, ceramics and semiconductors. An abrasive slurry or paste

is used to accelerate the cutting action.

-

- The most significant detail of the drilled

hole is the groove that is cut deeper through the quartz than the feldspar.

Quartz crystals are employed in the production of ultrasonic sound and,

conversely, are responsive to the influence of vibration in the ultrasonic

ranges and can be induced to vibrate at high frequency. In machining granite

using ultrasonics, the harder material (quartz) would not necessarily offer

more resistance, as it would during conventional machining practices. An

ultrasonically vibrating tool-bit would find numerous sympathetic partners

while cutting through granite, embedded in the granite itself! Instead

of resisting the cutting action, the quartz would be induced to respond

and vibrate in sympathy with the high frequency waves and amplify the abrasive

action as the tool cut through it.

-

- The fact that there is a groove may be

explained several ways. An uneven flow of energy may have caused the tool

to oscillate more on one side than the other. The tool may have been improperly

mounted. A buildup of abrasive on one side of the tool may have cut the

groove as the tool spiraled into the granite.

-

- That the hole and the core have tapered

sides is perfectly normal if we consider the basic requirements for all

types of cutting tools. This requirement is that clearance be provided

between the tool's non-machining surfaces and the workpiece. Instead of

having a straight tube, therefore, we would have a tube with a wall thickness

that gradually became thinner along its length. The outside diameter would

gradually get smaller, creating clearance between the tool and the hole,

and the inside diameter would get larger, creating clearance between the

tool and the central core. This would allow a free flow of abrasive slurry

to reach the cutting area. It would also explain the tapering of the sides

of the hole and the core. Since the tube-drill was a softer material than

the abrasive, the cutting edge would gradually wear away. The dimensions

of the hole would correspond to the dimensions of the tool at the cutting

edge. As the tool became worn, the hole and the core would reflect this

wear in the form of a taper.

-

-

- Mechanism For Ultrasonic Drilling.

-

- The spiral groove can be explained if

we consider one of the methods that is predominantly used to uniformly

advance machine components. The rotational speed of the drill is not a

major factor in this cutting method. The rotation of the drill is merely

a means to advance the drill into the workpiece. Using a screw and nut

method the tube drill could be efficiently advanced into the workpiece

by turning the handles (A) in a clockwise direction. The screw (B) would

gradually thread through the nut (C), forcing the oscillating drill into

the granite. It would be the ultrasonically induced motion of the drill

that would do the cutting and not the rotation. The latter would only be

needed to sustain a cutting action at the workface. By definition, therefore,

the process is not a drilling process, by conventional standards, but a

grinding process, in which abrasives are caused to impact the material

in such a way that a controlled amount of material is removed.

-

- The theory of ultrasonic machining resolves

all the unanswered questions where other theories have fallen short. Methods

may be proposed that might cover a singular aspect of the machine marks

and not progress to the method described here. It is when we search for

a single method that provides an answer for all the data that we move away

from primitive and even conventional machining and are forced to consider

methods that are somewhat anomalous for that period in history.

-

- On February 22, 1995 at 9 A.M. I had

my first experience of being on camera. It was interesting, and not at

all what I expected. I was standing in the central "King's Chamber"

of the only remaining wonder of the world, the Great Pyramid. Graham Hancock

and Robert Bauvall breezed patiently through the script with me, like old

pros, while I fumbled with instructions barked at me by Roel Oostra, the

producer from Netherlands Television. In a few sound bites, I had to convey

to an audience that there was something more to the sarcophagus, a large

red granite box which resides inside the chamber, than is evident to the

lay-person or casual observer.

-

- I was invited there by Robert Bauvall

(The Orion Mystery) and Graham Hancock (Fingerprints of the Gods) to participate

in a documentary which has been broadcast on several channels since then.

While there, I came across and was able to measure some artifacts produced

by the ancient pyramid builders which prove beyond a shadow of a doubt

that highly advanced and sophisticated tools and methods were employed

by this ancient civilization. Two of the artifacts in question are well

known, another is not, but it is more accessible, since it is laying out

in the open partly buried in the sand of the Giza plateau.

-

- For this trip to Egypt I had brought

along some instruments with which I had planned to inspect features I had

identified on my previous trip in 1986. The instruments were:

-

- 1. A "parallel": A flat ground

piece of steel about 6 inches long and 1/4 inch thick. The edges are ground

flat within .0002 inch.

-

- 2. An Interapid indicator. (Known as

a clock gauge by my British compatriots.)

-

- 3. A wire contour gage. A device used

by die sinkers to form around shapes.

-

- 4. Hard forming wax.

-

- I had brought along the contour gage

to check the inside of the mouth of the southern shaft inside the King's

Chamber. Unfortunately, I found out after getting there that things had

changed since I was there in 1986. In 1993, a German robotics engineer

named Rudolph Gantenbrink had installed a fan inside this mouth; therefore,

it was inaccessible to me and I was unable to check it.

-

- I had taken along the parallel for quick

checking the surface of granite artifacts to determine their precision.

The indicator was to be attached to the parallel for further inspection

of suitable artifacts. The indicator, didn't survive the rigors of international

travel, though, but the instruments I was left with were adequate for me

to form a conclusion about the precision to which the ancient Egyptians

were working.

-

- The first object I inspected was the

sarcophagus inside the second (Khafra's) pyramid on the Giza Plateau. I

climbed inside the box and, with a flashlight and the parallel, was astounded

to find the surface on the inside of the box perfectly smooth and perfectly

flat. Placing the edge of the parallel against the surface I shone my flashlight

behind it. No light came through the interface. No matter where I moved

the parallel, vertically, horizontally, sliding it along as one would a

gage on a precision surface plate I couldn't detect any deviation from

a perfectly flat surface. A group of Spanish tourists found it extremely

interesting, too, and gathered around me as I, quite animated, exclaimed

into my tape recorder, "Space-age precision!"

-

- The tour guides, at this point, were

becoming quite animated too. I sensed that they probably didn't think it

was appropriate for a live foreigner to be where they believe a dead Egyptian

should go, so, I respectfully removed myself from the sarcophagus and continued

my examination on the outside. There were more features of this artifact

that I wanted to inspect, of course, but didn't have the freedom to do

so. The corner radii on the inside appeared to be uniform all around with

no variation of precision of the surface to the tangency point. I was tempted

to take a wax impression, but the hovering guides with their baksheesh

expectancies inhibited this activity. (I was on a very tight budget.)

-

- My mind was racing as I lowered myself

into the narrow confines of the entrance shaft and climbed to the outside.

The inside of a huge granite box finished off to a precision that we reserve

for precision surface plates? How did they do this? And why did they do

it? Why did they find this piece so important that they would go to such

trouble? It would be impossible to do this kind of work on the inside of

an object by hand. Even with modern machinery it would be a very difficult

and complicated task!

-

- Petrie gave the dimensions of this coffer,

in inches, as - outside, length 103.68, width 41.97, height 38.12; inside,

length 84.73, width 26.69, depth 29.59. He stated that the mean variation

of the piece was .04 inch. Not knowing where the variation he measured

was, I'm not going to make any strong assertions except to say that it's

possible to have an object with geometry that varies in length, width and

height and still maintain perfectly flat surfaces. Surface plates are ground

and lapped to within .0001-0003 inch depending on the grade of surface

plate you buy. The thickness of them, though, may vary more than the .04

inch that Petrie noted on this sarcophagus.

-

- A surface plate, though, is a single

surface and would represent only one outside surface of a box. Not only

that, the equipment used to finish the inside of a box would be vastly

different than that used to finish the outside. The task would be much

more problematic. I was constructing in my mind the equipment I would need

to grind and lap the inside of a box to the accuracy I had witnessed and

produce a precise and flat surface to the point where the flat surface

meets the corner radius. There are physical and technical problems associated

with a task like this that are not easy to solve. One could use drills

to rough the inside out, but when it came to finishing a box of this size

with an inside depth of 29.59 inches, and maintain a corner radius of less

than 1/2 inch. There are some significant challenges to overcome.

-

- While being extremely impressed with

this artifact, I was even more impressed with other artifacts found at

another site in the rock tunnels at the temple of Serapeum at Saqqarra,

the site of the step pyramid and Zoser's tomb.

-

- I had followed Graham and Robert on their

trip to this site for a filming on Feb. 24, 1995. We were in the stifling

atmosphere of the tunnels, where dust kicked up from tourists lay heavily

in the still air. These tunnels contain 21 huge granite boxes. Each box

weighs an estimated 65 tons, and, together with the huge lid that sits

on top of them, the total weight of the assembly is around 100 tons. Just

inside the entrance of the tunnels there is a lid that had not been finished

and beyond this lid, barely fitting within the confines of one of the tunnels,

is a granite box that had also been rough hewn.

-

- The granite boxes are 13 ft. long, 7

1/2 ft. wide and 11 ft. high. They are installed in "crypts"

that were hewn out of the limestone bedrock at staggered intervals along

the tunnels. The floors of the crypts were about 4 ft. below the tunnel

floor, and the boxes were set into a recess in the center. Robert Bauvall

was addressing the engineering aspects of installing such huge boxes within

a confined space where the last crypt was located near the end of the tunnel;

a dead end with no room for the hundreds of slaves pulling on ropes, according

to theories proposed by those who believe that the ancient pyramid builders

were a primitive society.

-

- While Graham and Robert were filming,

I jumped down into a crypt and placed my parallel against the outside surface

of the box. It was perfectly flat. I shone the flashlight and found no

deviation from a perfectly flat surface. I clambered through a broken out

edge into the inside of another giant box and again, I was astonished to

find it astoundedly flat. I looked for errors and couldn't find any. I

wished at that time that I had the proper equipment to scan the entire

surface and ascertain the full scope of the work. Nonetheless, I was perfectly

happy to use my flashlight and straight edge and stand in awe of this incredibly

precise and incredibly huge artifact. Checking the lid and the surface

on which it sat, I found them both to be perfectly flat. It occurred to

me that this gave the manufacturers of this piece a perfect seal. Two perfectly

flat surfaces pressed together, with the weight of one pushing out the

air between the two surfaces! The technical difficulties in finishing the

inside of this piece made the sarcophagus in Khafra's pyramid seem like

a walk in the park.

-

- I was accompanied by Canadian researcher

Robert McKenty at this time. He saw the significance of the discovery and

was filming with his camera. At that moment I knew how Howard Carter must

have felt when he discovered Tutenkahmen's tomb. I yelled for Graham and

Robert to share the discovery, but was denied their presence by Roel Oostra,

who was working to a tight schedule and had to complete his filming.

-

- The dust filled atmosphere in the tunnels

was extremely unhealthy. I could only imagine what it would be like if

I was finishing off a piece of granite, regardless of what method I used,

how unhealthy it would be. Surely it would have been better to finish the

work in the open air? I was so astonished by this find that it didn't occur

to me until later that the builders of these relics, for some esoteric

reason, intended for them to be ultra precise. They had taken the trouble

to bring into the tunnel the unfinished product and finish it underground

for a good reason! It is the logical thing to do if you require a high

degree of precision in the piece that you are working. To finish it with

such precision at a site that maintained a different atmosphere and a different

temperature, such as in the open under the hot sun, would mean that when

it was finally installed in the cool, cave-like temperatures of the tunnel,

you would lose that precision. The granite would change its shape, or creep.

The solution, of course, was to prepare the precision surfaces in the location

in which they were going to be housed.

-

- This discovery, and the realization of

its critical importance to the artisans that built it, went beyond my wildest

dreams of discoveries to be made in Egypt. For a man of my inclination,

this was better than King Tut's tomb.

-

- The Egyptians' intentions with respect

to precision is perfectly clear. But for what purpose? In America today,

the cost of just the quarried granite would be $115,000.00. That's without

shipping costs and manufacturing costs, assuming there was equipment available

to machine it. I have contacted four precision granite manufacturers in

the US and haven't been able to find one who can do this kind of work.

-

- These artifacts need to be thoroughly

mapped and inspected with the following tools.

-

- 1. A laser interferometer with surface

flatness checking capabilities 2. An ultrasonic thickness gage to check

the thickness of the walls to determine their consistency to uniform thickness.

3. An optical flat with monochromatic light source. Are the surfaces really

finished to optical precision?

-

- With Eric Leither of Tru-Stone Corp,

I discussed in a letter the technical feasibility of creating several Egyptian

artifacts, including the giant granite boxes found in the bedrock tunnels

the temple of Serapeum at Saqqarra. He responded as follows.

-

- "Dear Christopher,

-

- First I would like to thank you for providing

me with all the fascinating information. Most people never get the opportunity

to take part in something like this.

-

- You mentioned to me that the box was

derived from one solid block of granite. A piece of granite of that size

is estimated to weigh 200,000 pounds if it was Sierra White granite which

weighs approximately 175 lb. per cubic foot. If a piece of that size was

available, the cost would be enormous. Just the raw piece of rock would

cost somewhere in the area of $115,000.00. This price does not include

cutting the block to size or any freight charges.

-

- The next obvious problem would be the

transportation. There would be many special permits issued by the D.O.T.

and would cost thousands of dollars. From the information that I gathered

from your fax, the Egyptians moved this piece of granite nearly 500 miles.

That is an incredible achievement for a society that existed hundreds of

years ago.."

-

-

- Eric went on to say that his company

did not have the equipment or capabilities to produce the boxes in this

manner. He said that his company would create the boxes in 5 pieces, ship

them to the customer, and bolt them together on site.

-

- The final artifact I inspected was a

piece of granite I quite literally stumbled across while strolling around

the Giza Plateau later that day. I concluded, after doing a preliminary

check of this piece, that the ancient pyramid builders had to have used

a three-axes machine to guide the tool that created it. Outside of being

incredibly precise, normal flat surfaces, being simple geometry, can justifiably

be explained away by simple methods. This piece, though, drives us beyond

the question normally pondered - "what tools were used to cut it?"

- to a more far reaching question.. - "what guided the cutting tool?"

-

- In answering this question, and being

comfortable with the answer, it is helpful to have a working knowledge

of contour machining.

-

- Many of the artifacts that modern civilization

produces would be impossible to produce using simple hand work. We are

surrounded by artifacts that are the result of men and women employing

their minds to create tools which overcome their physical limitations.

We have developed machine tools to create the dies that produce the aesthetic

contours on the cars that we drive, the radios we listen to and the appliances

we use.

-

- To create the dies to produce these items,

a cutting tool has to accurately and consistently follow a predetermined

contoured path in three dimensions. In some applications it will move in

three dimensions, simultaneously using three or more axes of movement.

The artifact that I was looking at required a minimum of three axes to

machine it. When the machine tool industry was relatively young, techniques

were employed where the final shape was finished by hand, using templates

as a guide. Today, with the use of precision computer numerical control

machines, there is little call for hand work. A little polishing to remove

unwanted tool marks may be the only hand work required. To know that a

piece has been produced on such a machine, therefore, one would expect

to see a precise surface with indications of tool marks that show the path

of the tool. This is what I found on the Giza Plateau, laying out in the

open south of the Great Pyramid about 100 yards east of the second pyramid.

-

- There are so many rocks of all shapes

and sizes lying around this area to the untrained eye, this one could easily

be overlooked. To a trained eye, it may attract some cursory attention

and a brief muse. I was fortunate that it both caught my attention, and

that I had the tools with which to inspect it.

-

- There were two pieces laying close together,

one larger than the other. They had originally been one piece and had been

broken. With the exception of my broken indicator gage, I found I needed

every tool that I had brought with me to inspect it. In inspecting this

piece, I was interested in the accuracy of the contour and its symmetry.

-

-

- Contoured Block of Granite - Giza

-

- What we have is an object that, three

dimensionally as one piece, could be likened to a small sofa. The seat

is a contour that blends into the walls of the arms and the back. The contour

was checked using the profile gage along three axes of its length, starting

at the blend radius near the back, and ending near the tangency point,

which blended smoothly where the contour radius meets the front. The wire

radius gage is not the best way to determine the accuracy of this piece.

When adjusting the wires at one position on the block and moving to another

position, the gage could be re-seated on the contour, but questions could

be raised as to whether the hand that positioned it compensated for some

inaccuracy in the contour. However, placing the parallel at several points

along and around the axes of the contour, I found the surface to be extremely

precise. At one point near a crack in the piece, there was light showing

through, but the rest of the piece allowed very little to show.

-

- During this time, I had attracted quite

a crowd. It's difficult to traverse the Giza Plateau at the best of times

without getting attention from the camel drivers, the donkey riders and

the purveyors of trinkets. It wasn't long after I had pulled the tools

out of my back-pack that I had two willing helpers, Mohammed and Mustapha,

who weren't at all interested in compensation. At least that's what they

told me. But I can honestly say that I lost my shirt on that adventure.

I had cleaned sand and dirt out of the corner of the larger block and washed

it out with water. I used a white T-shirt that I was carrying in my back-pack

to wipe the corner out so I could get an impression of it with forming

wax. Mustapha, talked me into giving him the shirt before I left. I was

so inspired by what I had found I tossed it to him.

-

- Mohammed held the wire gage at different

points along the contour while I took photographs of it. I then took the

forming wax and heated it with a match, kindly provided by the Movenpick

hotel, then pressed it into the corner blend radius. I then shaved off

the splayed part and positioned it at different points around. Mohammed

held the wax still while I took photographs. By this time there was an

old camel driver and a policeman on a horse looking on.

-

-

- Location where the wax impression was

taken.

-

-

- Verifying the radius at another location

-

- What I discovered with the wax was a

uniform radius, tangential with the contour and the back and side walls.

Returning to the US, I measured the wax and found, using a radius gage,

that it was a true radius and measured 7/16 inch.

-

- The side arm blend radius has a design

feature that is common engineering practice today. By cutting a relief

at the corner, a mating part that is to match, or butt up against the surface

with the large blend radius, may have a smaller radius. This feature provides

for a more efficient operation because it allows a cutting tool with a

large diameter, and, therefore, a large radius, to be used. With greater

rigidity in the tool, more material can be removed when taking a cut.

-

- I believe there is more, much more, that

can be gleaned using these methods of study. The Cairo Museum contains

many artifacts that will reveal much the same conclusion that I'm presenting

in this paper. In terms of a more thorough understanding of the level of

technology employed by the ancient pyramid builders, the implications of

these discoveries are tremendous. We are not only presented with hard evidence

that seems to have eluded us for decades and which provides further evidence

proving the ancients to be advanced, we are also provided with an opportunity

to re-analyze everything with a different perspective, from a different

angle. Understanding how something is made opens up a different dimension

when trying to determine why it was made.

-

- The precision in these artifacts is irrefutable.

Even if we ignore the question of how they were produced, we are still

faced with the question of why such precision was needed. The implications

of this question are just as profound.

-

- Revelation of new data, invariably spawns

new questions. In this case it's understandable to hear, "where are

the machines?"

-

- Machines are tools. The question should

be applied universally and can be asked of anyone who believes other methods

may have been used. The fact of the matter is that tools have not been

found to explain any theory! More than eighty pyramids have been discovered

in Egypt, and the tools that built them have never been found. Even if

we mis-guidedly accept the notion that copper tools are capable of producing

these incredible artifacts, the few copper implements that have been uncovered

do not represent the number of such tools that would have been used if

every stonemason who worked on the pyramids at just the Giza site owned

one. In the Great Pyramid alone, there are an estimated 2,300,000 blocks

of stone, both limestone and granite, weighing between 2* tons and 70 tons

each. That is a mountain of evidence with no tools surviving to explain

its creation.

-

- The principle of "Occam's Razor",

where the simplest means of manufacturing hold force until proven inadequate,

has held force over the pyramid builders methods, except there is one component

of this principle that has been lacking. If the simplest methods do not

satisfy the evidence, other less simple methods are considered, and so

on and so forth. There is little doubt that the capabilities of the ancient

pyramid builders have been seriously underestimated. The most distinct

evidence that I can relate is the precision and mastery of machining technologies

that are only now beginning to be re-invented. Some technologies the Egyptians

possessed still astound modern artisans and engineers primarily for this

reason.

-

- The development of machine tools has

been intrinsically linked with the availability of consumer goods and the

desire to find a customer. One reference point for judging a civilization

to be advanced has been our current state of manufacturing evolution. Manufacturing

is the manifestation of all scientific and engineering effort. For over

a hundred years this epoch has progressed exponentially. Since Petrie first

made his critical observations between 1880 and 1882, our civilization

has leapt forward at breathtaking speed to provide the consumer with goods,

all created by artisans, and still, over a hundred years after Petrie,

these artisans are utterly astounded by the achievements of the ancient

pyramid builders. They are astounded not so much by comparing their own

accomplishments with what they perceive a primitive society is capable

of, but by comparing these prehistoric artifacts with their own current

level of expertise and technological advancement.

-

- The interpretation and understanding

of a civilizations' level of technology cannot and should not hinge on

the preservation of a written record for every technique that they had

developed. The "nuts and bolts" of our society do not always

make good copy, and a stone mural will more than likely be cut to convey

an ideological message rather than the technique used to inscribe it. Records

of the technology developed by our modern civilization rest in media that

is vulnerable and could conceivably cease to exist in the event of a world

wide catastrophe, such as a nuclear war or another ice age. Consequently,

after several thousand years, an interpretation of an artisan's methods

may be more accurate than an interpretation of his language. The language

of science and technology doesn't have the same freedom as speech. So even

though the tools and machines have not survived the thousands of years

since their use, we have to assume, by objective analysis of the evidence,

that they did exist.

-

-

- Crooke's Tube.

-

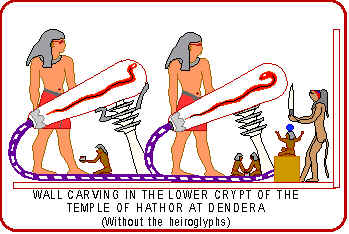

- Notwithstanding the previous argument,

the ancient Egyptians did cut a mural that, while it could be interpreted

as presenting a symbolic message, also describes a technology that was

being used by the contemporaries of the masons that carved it. Inscribed

into the wall in the lower crypt at the temple of Hathor at Dendera is

the representation of a machine.

-

-

Wall Carving At Dendera Courtesy: Christopher Dunn

-

-

- Go to Dendera to view a representation

of a Crooke's Tube! (Cathode Ray Tube.) It's not something you would use

to cut granite, but viewed within the context of modern scientific discovery,

the Crooke's tube is known as the device that triggered the discovery of

x-rays. The sketch seems to symbolize the medical profession. Put the two

snakes together and Caduceus comes to life, with representations of medicine

and the proffering of the scalpel. (Symbolizing the subjugation of exploratory

surgery to the power of new technology, the x-ray?) Machines did exist.

Of the kind that are in existence today, and even those we have yet to

develop.

-

- There is much to be learned from our

distant ancestors, but before that lesson will come to us, we need to open

our minds and accept that there have existed on the earth, civilizations

with technology that, while different from our own, and in some areas possibly

not as advanced, had developed some manufacturing techniques that are as

great or even greater. As we assimilate new data and new views of old data,

it is wise to heed the advice Petrie gave to an American who had visited

him during his research at Giza. The American expressed a feeling that

he had been to a funeral after hearing Petrie's findings, which had evidently

shattered some favorite pyramid theory at that time. Petrie says, "By

all means let the old theories have a decent burial; though we should take

care that in our haste none of the wounded ones are buried alive."

-

- Chris Dunn can be contacted by email

at: cdunn1546@aol.com

|