![]()

Concerns

Regarding The Ebola Virus

|

The CDC recently declared: “Diagnosing Ebola in a person who has been infected for only a few days is difficult, because the early symptoms, such as fever, are nonspecific to Ebola infection and are seen often in patients with more commonly occurring diseases, such as malaria and typhoid fever.” Only a sin of omission then would explain why anyone or any group would not want to specifically mention the most commonly occurring cause of infectious death in Africa — tuberculosis — whose sky-high rates in West Africa make Ebola look like a dropper-full of water squeezed into the Mississippi. If by October, 2014, Ebola had laid claim to what some say is 3,000-plus deaths since its February outbreak, certainly this ought to be weighed in the light of the approximately 600,000 Africans killed by TB in the same time-frame. Furthermore, although TB incidence is decreasing globally, incidence rates are increasing in most of West Africa1 — ground zero for the current Ebola outburst. Just as curiously, almost half of all TB cases in the West African Ebola zone are caused by an unusual, yet just as deadly member of tubercular family, Mycobacterium africanum — a strain of tuberculosis exclusive to West Africa, which is fast becoming a microbe of great public — and now possibly global concern. Surely the CDC is aware that there is not a sign or symptom of Ebola, including its hemorrhagic tendencies that cannot be found in acute disseminated miliary (blood-bourne) tuberculosis, once called “galloping consumption” — the single most feared form of the disease ever. And most likely it is also aware that such tuberculosis has its own viral-like forms, some of which can simulate the Ebola. Such viral TB is generally acknowledged to be TB’s preferred form — as a survival strategy to storm any inclement conditions the microbe might find itself in.2 Then why did the CDC not mention TB, by name, in their short-list of possibilities that could cause Ebola-like symptoms? If such oversight stopped there it would be unremarkable, but it seems to have been carried over in the very design of the most recent diagnostic tests issued to detect Ebola. _________________________________________________ In September of 1978, about 40 years ago, a team — including a 27-year-old medical graduate, training as a clinical microbiologist at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium, received a blue thermos from Zaire. It was filled with the two 5ml. clotted blood specimens of an African-based Flemish nun. The Belgium doctor who sent it, Jacques Courteille, practicing in Kinshasa, included a note saying that he was at a complete loss for the nun’s mysterious, yet deadly illness. Also, could the samples be tested for Yellow Fever? This thermos had traveled from Zaire’s capital city of Kinshasa, on a Sabena commercial flight to Belgium — inside its deliverer’s hand luggage. When the samples were received, Peter Piot, the 27-year-old medical graduate and his colleagues, among other things, placed the blood samples under an electron microscope. Piot: “We saw a gigantic worm like structure — gigantic by viral standards. It’s a very unusual shape for a virus, only one other virus looked like that and that was the Marburg virus.” But the new “virus” needed a name. Piot relates the interesting tale of how Ebola came to be named as Ebola: "On that day our team sat together late into the night we had also had a couple of drinks discussing the question. We definitely didn't want to name the new pathogen "Yambuku virus", because that would have stigmatized the place forever. There was a map hanging on the wall and our American team leader suggested looking for the nearest river and giving the virus its name. It was the Ebola River. So by around three or four in the morning we had found a name. But the map was small and inexact. We only learned later that the nearest river was actually a different one. But Ebola is a nice name, isn't it?”3 Depends upon how you look at it. Piot’s specimens proved negative for Yellow Fever and he mentions that the tests for Lassa fever and typhoid were also negative. What, then, could it be? Piot: “To isolate any virus material” small amounts of the blood samples were injected into VERO cells and into mice. Several of these mice subsequently and abruptly died — “a sign that a pathogenic virus was probably present in the blood samples that we had used to inoculate them.” The fact that the mice died did not mean that it was at the hands of a “pathogenic virus”. Piot’s boss, Stefaan Pattyn, who Piot admitted “could be a bit of a bully”, supposedly specialized in the study of mycobacteria — tuberculosis and leprosy, yet seemed unaware of the hemorrhagic consequences of acute TB, nor had he taken the time to use special stains and cultures to detect its viral cell-wall-deficient forms. Instead Pattyn followed his current passion. He had recently worked in Zaire for six or seven years and exotic viral illnesses were now “right up his alley”. So Pattyn’s team likewise never really considered a strain of acute milliary TB or its viral cell-wall-deficient forms in his rule-outs for an acute hemorrhagic or epidemic fever — among them Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium africanum. ______________________________________ The Ebola of its day on steroids, “galloping” acute consumptive tuberculosis could kill in days — the mere memory of which, just a few generations ago, brought terror to the faces of those who had witnessed and were describing it. Dubos made clear that "galloping consumption" was not an isolated, but a frequent diagnosis in the 19th and early 20th centuries.4 And despite persistent myths to the contrary, in the early phase of any new TB epidemic from a new and virulent strain, tuberculosis manifests itself as an acute disease and only much later as the chronic pulmonary tuberculosis that we know in today’s western world. An example of this can be found in the high mortality during the 1918 influenza pandemic, when African-Americans were brought to fight in France during World War I — large numbers of them dying from a fast-tracked tubercular "galloping consumption." Many often underestimate the speed, contagiousness and ferocity of a TB epidemic. Khomenko's 1993 study5 should have cemented the notion that the explosive contagiousness of just such Ebola and influenza-like viral forms of tuberculosis are exactly the stuff that previous epidemics and pandemics could have been made of. But it didn’t.

In the US, the CDC and NIH seemed to feel differently, ignoring the historic possibility. There was much the same viral passion, at that time over “Influenza", when in 1990, a new multi-drug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis outbreak took place in a large Miami municipal hospital. Soon thereafter, similar outbreaks in three New York City hospitals left many sufferers dying within weeks. By 1992, approximately two years later, drug-resistant tuberculosis had spread to deadly mini-epidemics in seventeen US states, and was reported, not by the American, but the international media, as out of control. Viral forms of swine, avian and human TB can be transmitted from one species to another. So can exotic strains of tuberculosis and Mycobacterium africanum, imported into the United States through countries such as Liberia. By 1993 the World Health Organization (WHO) had proclaimed tuberculosis a global health emergency6. That emergency has never been lifted. _______________________________________________ Anderson pointed out that such acute, untreated disseminated, “galloping”, blood-dispersed TB could kill in hours or days7 — its mortality, according to Saleem and Azher even today approaching 100%.8 Ebola itself can take up to a month to kill its victims, said Ben Neuman, an expert in viruses at Britain’s Reading University — although there are many cases that also kill in hours or days. Not only were tubercular hemorrhaging and fever both mentioned by Fox9, but hemorrhaging of the serous cavities, the gums, and the nose, into the joints, the skin, and the bowels. Appleman10, in the American Journal of Ophthalmology, considering massive spontaneous hemorrhages into the vitreous, mentions that Axenfeld considered acute tuberculosis an important possibility in the rule-out for bleeding into the eye. Coughing-up blood has always been a well-known scenario for TB. Hemorrhages of significance from the ear secondary to tuberculous otitis media are also on record.11 And the possibility of acute miliary tuberculosis attacking the bone marrow and through fibrosis causing a partial shutdown of platelets — leading to its various hemorrhagic manifestations has always been present. Even today, bone marrow biopsy is at times a valuable diagnostic test for tubercular involvement. In addition Extrapulmonary (outside of the lungs) tuberculosis is the most frequent cause of a prolonged Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) and has been for a long, long time.12 ____________________________________________________________________________

Meanwhile, The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) latest “Situation Report” summed-up that although the rate of Ebola infections were picking up speed at an alarming rate in West Africa, the fatality rate was 53% overall, ranging from 64% in Guinea to just 39% in Sierra Leone. If this 53% figure was designed to make the situation more bearable, it hardly achieved its goals. ___________________________________________________

Critics claimed that the two PCR systems to be used for Ebola testing in such “emergency situations” have never tested negative, and that besides, the tests are unapproved. But there is more. While an instruction booklet issued by the FDA14 showed impressive results for detecting and thereby being positive for known “Ebola” samples — it sadly failed in its inadequate selection of those pathogen’s that might be cross-reacting and therefore making for false positive Ebola tests. The CDC’s instruction booklet, Version 2, that accompanied the new Ebola assay mentions: “9.2.2.2 Bacterial Cross-Reactivity: Bacterial cross-reactivity of the EZ1 assay was evaluated by testing purified nucleic acid of bacteria that potentially could be infecting the majority of the population. No cross-reactivity was observed in the human DNA or any of the bacteria tested (Table 51).”14 [Bold print theirs] Yes. The only problem being that a glance at Table 51 shows practically every bacteria in existence except for the one subset of pathogens “that potentially could be infecting the majority [of West Africa’s] population” and those pathogens are again — Mycobacteria tuberculosis and its related Mycobacterium africanum. Such diversion is no trivial point. In the past, as the first scientist to propose HIV-virus testing, veterinarian Max Myron Essex knew that tuberculosis and its allied mycobacteria gave a false positive for the HIV virus in his tests in almost 70% of cases. Such cross-reactivity between HIV and tuberculosis was so significant, that it forced Essex15 and his protégé, Oscar Kashala, to warn that both the HIV screening test, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and western blot results “should be interpreted with caution when screening individuals with M. tuberculosis or other mycobacterial species.”15 This, of course, automatically meant throwing away HIV serum diagnostics for, according to WHO, at least a third of the people in the known world that WHO (The World Health Organization) has proclaimed presently harbor tubercular infection. So why then was Mycobacterium tuberculosis noticeably excluded from the CDC’s Table 51 and not included in those pathogens tested for cross-reacting and therefore giving false positive tests for the Ebola? Did the originally panel (Version 1?) chosen by government scientists actually include Mycobacterium tuberculosis and related microbes in its design — only to find that indeed these mycobacteria caused positive tests for Ebola as in the HIV affair? Did they feel that such results might muddy the waters, be too difficult to explain, and subsequently remove them? This is not known.

Therefore are the HIV drugs working against an “Ebola” which is estimated to have killed well over 3,000 African’s so far this year or the TB that killed 600,000 Africans in that same window? There still remains much work ahead to determine this. Antiretrovirals have major side effects. _________________________________________________

“Angola is in the grip of the world's worst ever outbreak of the Marburg virus. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 5 April, 156 of the 181 people reported infected have died. The Ebola-like virus causes a fever that, in fatal cases, is usually accompanied by severe internal bleeding and shock. There is no vaccine or medical treatment and up to 80 per cent of infected people die within three to seven days. Three-quarters of those affected are children under five. Diagnosing an infection with the Marburg virus can be difficult as its initial symptoms are similar to those of malaria or tuberculosis. They include diarrhea, stomach pains, nausea, and vomiting and severe chest pains.”17 The heavy mortality and morbidity under the age of five with Marburg brings to mind specifically a tubercular involvement, in which most children are affected also in the same age group. What has been called ‘The Golden Age of Resistance’ against TB mortality has always been, for unknown reasons, ages six thru fifteen.4 __________________________________________

To some it might be considered wormlike, to others serpentine.

Figure 1. The serpentine form of the Ebola Virus. Courtesy: CDC Frederick A. Murphy

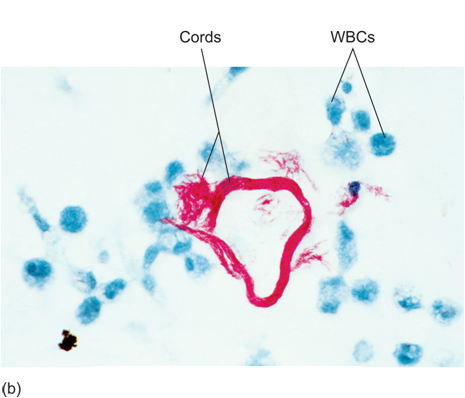

Figure 2. The serpentine form of ‘Cords’ of lethal tubercle bacilli X126.

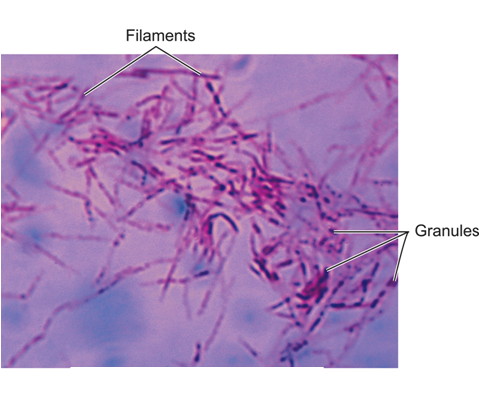

Figure 3. Again, Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, also of Serpentine or “worm-like” form in its deadly cord formation. _________________________________________________________ Both the Ebola virus and the Marburg virus are called Filoviruses because they form filamentous infectious viral particles. Filoviruses, however, are not alone. Mycobacterium. tuberculosis, which commonly lodges in and multiplies in the very same white cell defenders of our body (called macrophages) — also become filamentous once inside a macrophage.18

Figure 4. Filamentous forms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. __________________________________________________

WHO’s statement is misleading. As far back as 1995 the ability of Ebola to aerosolize or spread through airborne transmission was reported, studied and confirmed.19,20 Ebola, is a communicable airborne infection, just like tuberculosis.

“Ebola virus has been found in African monkeys, chimps and other nonhuman primates such as fruit bats in Africa. A milder strain of Ebola has been discovered in monkeys and pigs in the Philippines.”21

Figure

5. The African Fruit Bat Early studies suggested that the new strain of Ebola had emerged in West Africa, but according to epidemiologist Fabian Leendertz, a disease ecologist at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin, who led the large team of scientists to Guinea, it is likely the virus in Guinea is closely related to the one known as the Zaire Ebola Virus, identified more than 10 years ago in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But the same fruit bats can carry mycobacteria from the mycobacterial tuberculosis complex.22,23,24

_______________________________________________

Figure 6. Present Distribution of Ebola Deaths; “Probable, Confirmed and Suspected”, in West Africa.

So what is the take-home message here? At best that “Ebola-like” does not always mean Ebola; at worst that Ebola does not mean Ebola.

Dr. Lawrence Broxmeyer, MD © U.S. Library of Congress All rights reserved October, 2014 See Also:

Broxmeyer, L. AIDS: What the Discoverers of HIV Have Never Admitted: Latest Edition. 2014, July. 142 pp. http://www.amazon.com/AIDS-Discoverers-Admitted-Latest-Edition/dp/1495457044/ref=sr_1_fkmr0_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1412375194&sr=8-3-fkmr0&keywords=Lawrence+Broxmeyer+AIDS%3A+What+the+discovers+of+HIV+have+never+admitted |

| Donate

to Rense.com

Support Free And Honest

Journalism At Rense.com |

Subscribe

To RenseRadio!

Enormous Online Archives,

MP3s, Streaming Audio Files,

Highest Quality Live Programs |