|

The

cause of breast cancer is unknown, but over the past century various

controversial scientists have implicated bacteria as the causative agent

[1-8]. Despite this cancer microbe research, the bacterial theory of

cancer has been widely rejected. This report suggests that the elimination

of bacteria as breast cancer-causing agents was premature; and that

new research gives additional credence to bacteria causing breast cancer.

The

findings of the Human Microbiome Project, launched in 2006,

indicate the human body contains 100 trillion microbes, most of

which are bacteria. In fact, 90% of the cells of the body are not

human cells, but microbial cells. The precise role these bacteria

play in cancer is not known, nor has it been studied.

In

addition, only recently have we learned that various organs and

tissue of the human body are not

sterile. Previously it was believed that such tissue was devoid of

bacteria. Now various bacteria have been detected by molecular

biology techniques and properly stained microscopic examination. In

2014 Urbaniak et al. [9] found a diverse population of bacteria in

breast tissue, the details of which can be found online at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4018903/

There

are many different risk factors postulated for breast cancer, but

according to the National Cancer Institute, breast cancer is a

genetic disease caused by certain changes to genes that control the

way our cells function, especially how they grow and divide. These

changes include mutations in the DNA that make up our genes. In this

regard, it is well-accepted that bacteria frequently “swap genes”

with one another. More controversial is recent research indicating

that bacteria can also exchange genes with human cells, especially

cancer cells. For this reason, the presence of bacteria in cancer

should be taken seriously as a source of genetic alteration and

cancer production [10].

Bacteria found in cancerous

tissue have generally been dismissed as “secondary invaders” of tissue

weakened by cancer. Bacteria cultured from cancerous tissue are often

interpreted as “laboratory contaminants” of no etiologic consequence.

With the new knowledge that various bacteria are universally present

in breast tissue, their presence in cancer can no longer be assumed

to be “secondary.” In fact, bacteria are always present before

the cancer process is initiated. The reported microbiology of cancer

indicates that cancer bacteria often grow in the lab as common bacteria,

such as staphylococcal, streptococcal, and corynebacteria-like bacteria.

Because bacteria are generally thought to play no role in cancer, such

isolates are generally regarded as “contaminants” having no significance.

According to

cancer microbe researchers, the germ is a pleomorphic,

intracellular and extracellular microorganism that can be detected in

cancerous tissue by the use of special tissue stains, particularly

the acid-fast stain traditionally used for the detection of TB

mycobacteria. The common form in tissue is the round

staphylococcus-like coccoid form. These coccoid forms vary in size

from barely visible “granules” up to much larger “globoid”

forms [1,2,4,7].

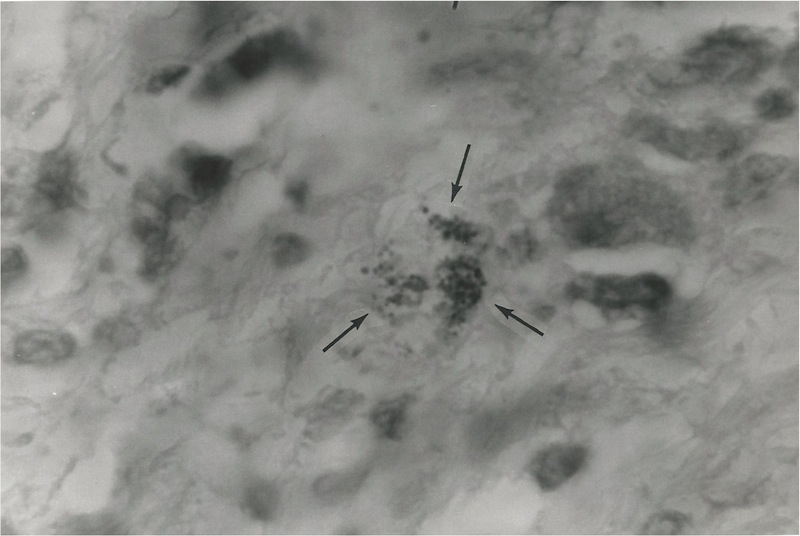

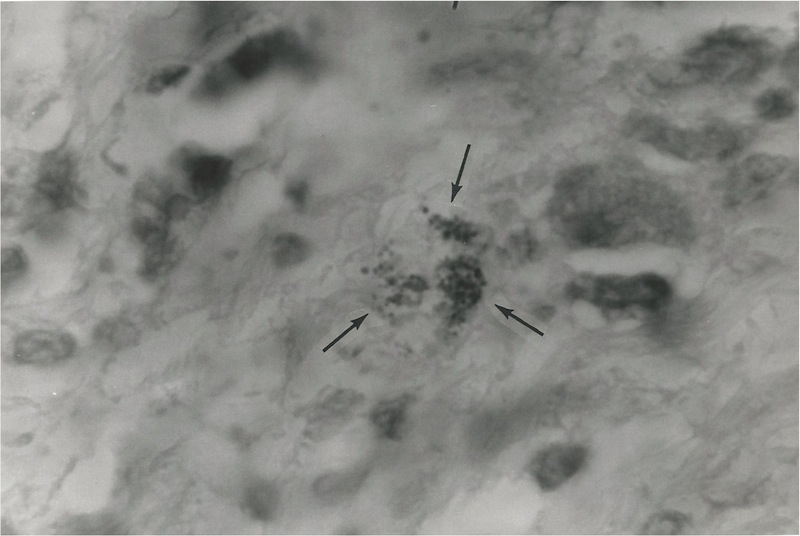

The following

5 photos show the appearance of these coccoid forms in a case of intraductal

breast cancer previously reported in 1981 [8].

Figure

1. Tissue section of breast cancer showing tumor cells and a nest of

extracellular coccoid forms and still smaller “granular” forms, some

of which are barely visible. Intensified Kinyoun (acid-fast) stain,

magnification x 1000, in oil.

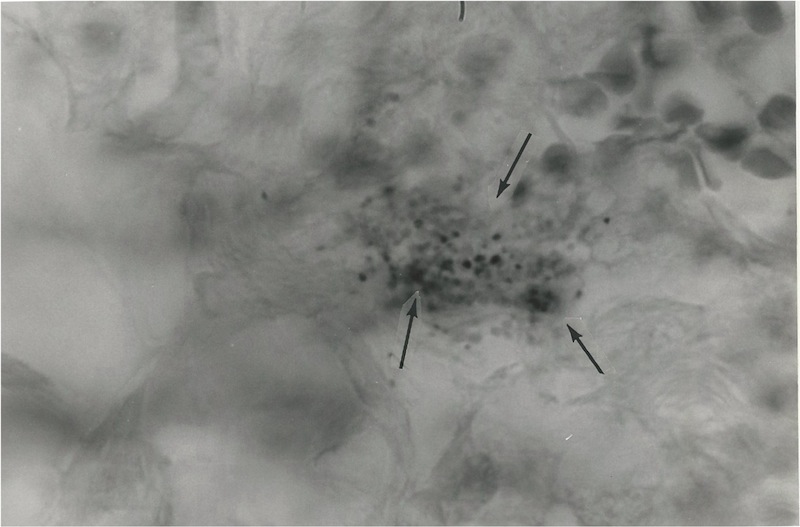

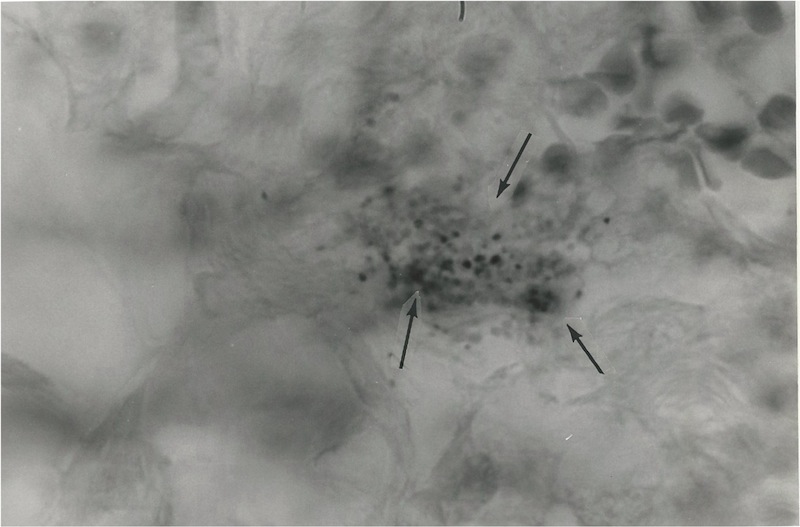

Figure

2. Tissue section of breast cancer showing a nest of extracellular variably-sized

coccoid forms. A collection of red blood cells is seen in the upper

right. Intensified Kinyoun stain, x 1000, in oil.

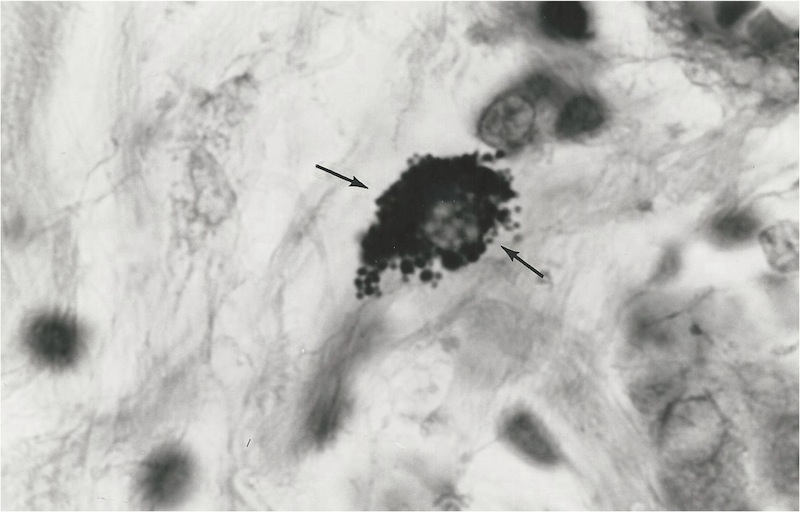

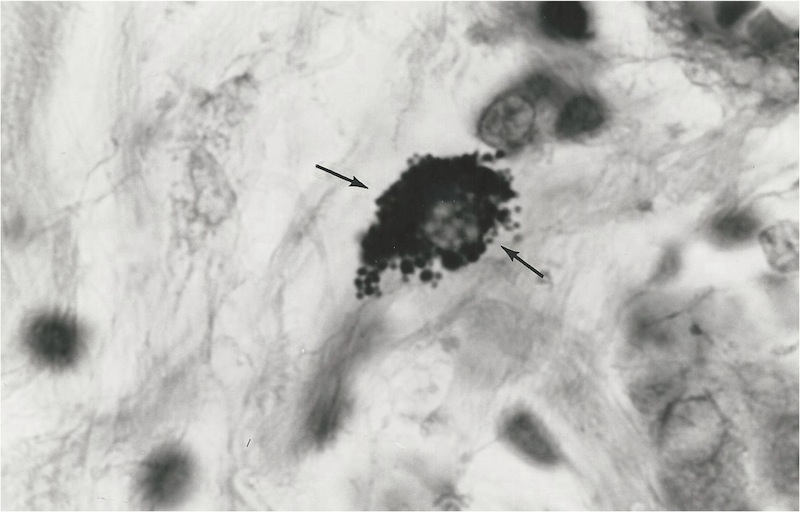

Figure

3. Tissue section of breast cancer showing intracellular variably-sized

coccoid forms and larger globoid forms. Intensified Kinyoun stain. x

1000, in oil

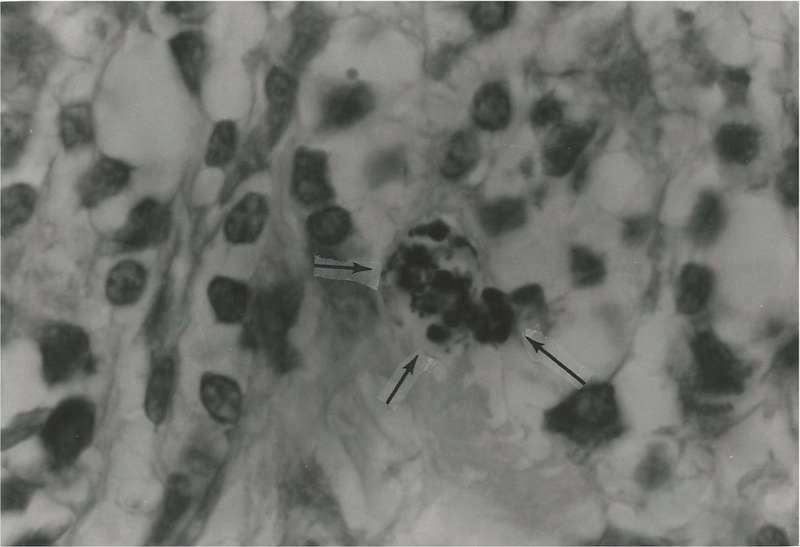

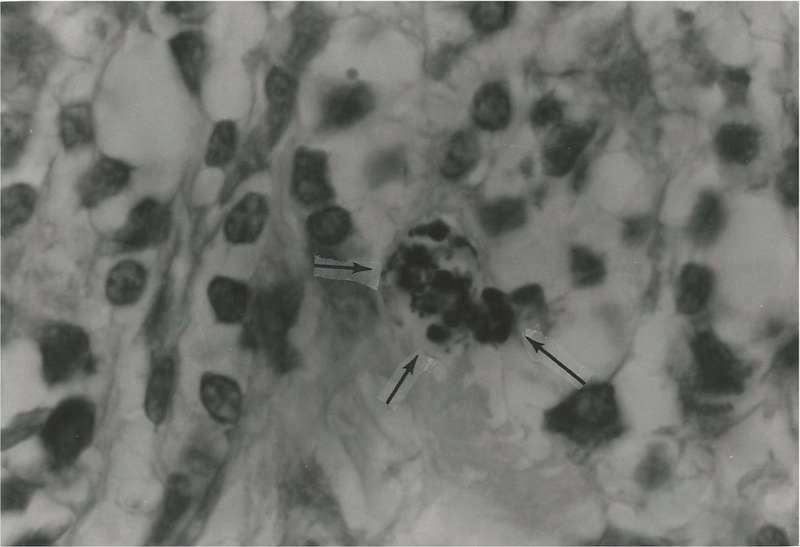

Figure

4. Tissue section of breast cancer showing a nest of variably-sized

coccoid forms ranging in size from barely visible "granules"

up to the size of ordinary staphylococci and still larger "globoid"

forms. The size range and pleomorphic nature of the round forms suggest

growth forms of so-called cell wall deficient bacteria. Intensified

Kinyoun stain, mag x 1000, in oil.

Figure

5. Smear of Staphylococcus

epidermidis

cultured from a biopsy taken from a metastatic nodule when the original

breast cancer tumor metastasized to the skin. All the coccal forms in

this photo are the size of ordinary cocci, except for two much larger

forms consistent with the size of globoid forms. Compare the size and

shape of the coccoid forms found in the breast tumor in photos 1-4 with

the size and shape of the staphylococci grown in the laboratory. Gram

stain, x 1000, in oil.

Why have bacteria in breast tissue and breast

cancer been ignored or overlooked for a century? One explanation is

that the pathologists’ routine tissue staining methods for

cancer diagnosis does not demonstrate bacteria well. Cancer microbe

researchers discovered that special stains were required,

particularly the acid-fast stain [1,4,7]. Also the cancer microbe is

pleomorphic and can exhibit various guises in tissue and in the

laboratory [7]. Such bacteria have been described as cell wall

deficient bacteria, and there is also an ultramicroscopic viral-size

growth form that can pass through lab filters designed to hold back

bacteria [4].

For

more details on cancer microbe research, see my articles on

rense.com, including ‘Bacteria cause cancer; The microscopic

evidence’ and ‘Cancer is an infection caused by tuberculosis-type

bacteria’ at http://www.rense.com/general95/bacmicro.html

and http://www.rense.com/general80/canc.htm

Currently,

there is a slight renewal of interest in bacteria and cancer. In an

editorial entitled ‘Cancer and the microbiome’, published in

April 2015 in Science,

Dr. Wendy Garrett explains how microbes could influence

carcinogenesis by causing changes in cell proliferation and death;

through immune system interference; and via metabolism of food,

pharmaceuticals, and host-produced chemicals [11].

At

present, the serious research of cancer microbe workers that took

place decades ago has been largely forgotten, and rarely, if ever,

cited by current researchers of the microbiome. This is a tragic (as

well as unscientific) situation.

Bacteria are intimately associated with inflammation

in the body; and inflammation precedes cancer. Bacteria are always present

in breast tissue. Thus, their presence always precedes the growth of

cancer. Bacteria should surely be given some renewed consideration as

a cause of breast cancer.

SELECTED

REFERENCES

1.

Wuerthele Caspe (Livingston) V, Alexander-Jackson E, Anderson JA, et

al: Cultural properties and pathogenicity of certain microorganisms

obtained from various proliferative and neoplastic diseases. Amer

J Med Sci 220:628-646,

1950.

2.

Alexander-Jackson

E: A specific type of microorganism isolated from animal and human

cancer: Bacteriology of the organism.Growth 18:37-51,

1954.

3.

Diller IC: Growth and morphologic variability of pleomorphic,

intermittently acid-fast organisms isolated from mouse, rat, and

human malignant tissues. Growth 26:181-209,

1962.

4.

Wuerthele-Caspe Livingston V, Alexander-Jackson E: An experimental

biologic approach to the treatment of neoplastic disease.J

Amer Med Women's Assn 20:858-866,

1965.

5.

Seibert FB, Farrelly FK, Shepherd CC: DMSO and other combatants

against bacteria isolated from leukemia and cancer patients. Ann

NY Acad Sci 141:175-201,

1967.

6.

Seibert FB, Yeomans F, Baker JA, et al: Bacteria in tumors. Trans

NY Acad Sci 34(6):504-533,

1972.

7.

Wuerthele Caspe Livingston V, Livingston AM: Some cultural,

immunological, and biochemical properties of Progenitor

cryptocides. Trans

NY Acad Sci 36(6):569-582,

1974.

8.

Cantwell AR Jr, Kelso DW: Microbial findings in cancer of the breast

and in their metastases to the skin. J

Dermatol Surg Oncol 7:483-491,

1981.

9.

Urbaniak C, Cummins J, Brackstone M, et al. Microbiota of human

breast tissue. Appl

Environ Microbiol

(2014) May;80(10):3007-14. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00242-14. Epub 2014 Mar

7.

10.

Riley DR, Sieber KB, Robinson KM, et al. Bacteria-Human Somatic Cell

Lateral Gene Transfer Is Enriched in Cancer Samples. Eisen JA, ed.

PLoS

Computational Biology.

2013;9(6):e1003107. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003107.

11.

Garrett WS. Microbial dysbiosis is associated with breast cancer. PLoS

One

(2014); 9(1): e83744. Published online 2014 Jan 8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083744.

[Alan

Cantwell is a retired dermatologist. He is the author of The

Cancer Microbe and Four Women Against Cancer, available from amazon.com

Email:

AlanRCan@aol.com]

|