-

- While the cutting techniques of the ancient pyramid builders

have been an ongoing topic for debate, they have not received the same

attention and controversy as the methods that were used to lift and transport

cyclopean blocks of stone. Egyptologists and orthodox believers of primitive

methods argue that the huge blocks were moved and positioned using only

manpower, but experts in moving heavy weights using modern cranes throw

doubt on their theory.

-

- My company installed a hydraulic press that weighs sixty-five

tons. In order to lift it and lower it through the roof, they had to bring

in a special crane. The crane was brought to the site in pieces transported

from eighty miles away over a period of five days. After fifteen semi-trailer

loads, the crane was finally assembled and ready for use. As the press

was lowered into its specially prepared pit, I asked one of the riggers

about the heaviest weight he had lifted. He claimed that it was a 110-ton

nuclear power plant vessel. When I related to him the seventy- and two

hundred-ton weights of the blocks of stone used inside the Great Pyramid

and the Valley Temple, he expressed amazement and disbelief at the primitive

methods Egyptologists claim were used.

-

- For many of us to whom the Egyptologists' orthodox theory

seems implausible, it is enough just to argue the issue from a logical

standpoint. For others, the debate becomes more meaningful when a proposed

alternate method is demonstrated and proven to be successful. For that

proof we must turn to the one man in the world who, by demonstration, has

supported the claim, "I know the secret of how the pyramids of Egypt

were built!" That man was Edward Leedskalnin, an eccentric Latvian

who immigrated to the United States and who is now deceased. But he left

many intriguing clues that persuade us he may indeed have known such secrets.

-

-

-

- Leedskalnin devised a means to single-handedly lift and

maneuver blocks of coral weighing up to thirty tons. In Homestead, Florida,

using his closely guarded secret, he was able to quarry and construct an

entire complex of monolithic coral blocks in an arrangement that reflected

his own unique character. On average, the weight of a single block used

in the Coral Castle was greater than those used to build the Great Pyramid.

He labored for twenty-eight years to complete the work, which consisted

of a total of 1,100 tons of rock. What was Leedskalnin's secret? Is it

possible for a 5-foot tall, 110-pound man to accomplish such a feat without

knowing techniques that are undiscovered to our mainstream contemporary

understanding of physics and mechanics?

-

-

-

-

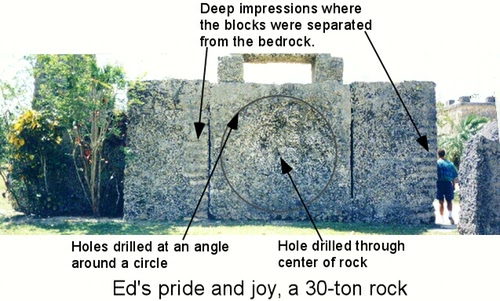

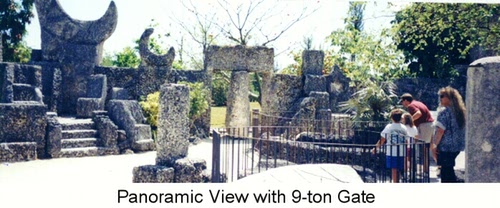

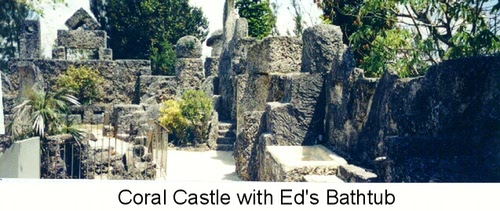

- Leedskalnin was a student of the universe. Within his

castle walls, he had a 22-ton obelisk, a 22-ton moon block, a 23-ton Jupiter

block, a Saturn block, a 9-ton gate, a coral rocking chair that weighed

3 tons, and numerous other items. A huge 30-ton block, which he considered

to be his major achievement, was crowned with a gable-shaped rock. Leedskalnin

somehow single-handedly created and moved these massive objects without

the benefit of cranes and other heavy machinery, a feat that astounds many

engineers and technologists, who compare these achievements with those

employed by workers handling similar weights in industry today.

-

-

-

-

-

- Leedskalnin's castle was not always located in Homestead,

Florida. He thought he had found his Shangri-la near Florida City and was

happily working away on his rock garden until one night several thugs attacked

him. Being a small man, he was an easy mark for these cowards, and he became

a changed man after the trauma. Such was his concern that he became obsessed

with moving his rock garden to a safer area. To assist him in the effort,

he contracted with a local truck driver to haul his large rocks from Florida

City to Homestead. As they prepared to load a 20-ton obelisk onto the truck,

Leedskalnin asked the truck driver to leave him alone for a moment. Once

out of sight, the truck driver heard a loud crash. Hurrying back to his

truck, he was stopped in his tracks by the sight before him, hardly believing

his eyes. He had returned just in time to see Leedskalnin dusting off his

hands, the huge obelisk loaded and weighing down his flatbed.

-

- Once in Homestead, the trucker was asked to leave his

flatbed overnight and return in the morning. He was doubtful that Leedskalnin

would be able to fulfill his promise that the obelisk would be off the

truck and erected in the place he had set out for it. It's a good thing

the truck driver did not bet money against Leedskalnin's ability to fulfill

his word, because when he returned the following morning, Leedskalnin had

moved the monolith into position, just as he had promised.

-

- For his stupendous feats of construction engineering,

Leedskalnin received attention not only from engineers and technologists,

but from the United States Government, who paid him a visit, hoping to

be enlightened. Leedskalnin received the officials gracefully, but they

left none the wiser. In 1952, falling ill and on his last legs, Leedskalnin

checked himself into the hospital and slipped away from this life, taking

his secrets about moving massive objects with him.

-

- If we assume that Leedskalnin and the ancient pyramid

builders were using similar techniques, we must reevaluate the requirements

for the man-hours necessary to construct the Great Pyramid. Estimates provided

by Egyptologists for the number of workers that built the Great Pyramid

range between 20,000 and 100,000. Based on the abilities of this one man,

quarrying and erecting a total of 1,100 tons of rock over a time span of

twenty-eight years, the 5,273,834 tons of stone built into the Great Pyramid

could have been quarried and put in place by only 4,794 workers. If we

figure in the efficiencies to be gained from working in a team and the

division of labor, we can reduce the number of workers and/or shorten the

time needed to complete the task. Let us not forget the estimate given

by Merle Booker (deceased), of the Indiana Limestone Institute, for the

delivery of enough limestone to build a Great Pyramid. Using the same criteria-with

respect to size and quantity-as the ancient builders, but using modern

equipment, Booker estimated that all thirty-three Indiana limestone quarries

would have to triple their average output to produce the stone. His estimate

did not factor in any equipment failures, labor disputes, or acts of God.

He estimated that twenty-seven years after the order was placed, the last

stone would have been delivered! These numbers put Leedskalnin's accomplishments

in their proper perspective.

-

-

-

-

-

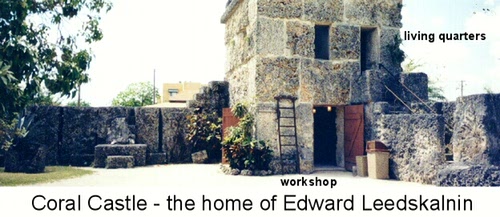

- I first visited Coral Castle in 1982 while vacationing

in Florida. It soon became clear to me that Leedskalnin's claim was accurate-he

did indeed know some secrets, perhaps even the very ones used by the ancient

Egyptians. I returned to Homestead again in April 1995 to refresh my memory

and, specifically, to closely examine a device that, in 1992, fueled a

discussion between an engineer colleague, Steven Defenbaugh, and myself.

Our discussion resulted in a speculation as to the methods that Leedskalnin

had used.

-

- Leedskalnin took issue with modern science's understanding

of nature. He flatly stated that scientists are wrong. His concept of nature

was simple: All matter consists of individual magnets, and it is the movement

of these magnets within materials and through space that produces measurable

phenomena-that is, magnetism and electricity and so on.

-

- Whether Leedskalnin was right or wrong in his assertions,

from his simple premise he was able to devise a means to single-handedly

elevate and maneuver large weights, which would be impossible using conventional

methods. There is speculation that he was employing electromagnetism to

eliminate or reduce the gravitational pull of the Earth. These speculations

are entertained by some and scoffed at by others whose feet are firmly

planted in the "real world."

-

- While at Coral Castle, I commented to a lady standing

in Leedskalnin's workshop that it was quite a feat he had performed, and

asked if she had any idea how he had done it. Fixing me with a measured

look, she said, "Through the application of physics and mechanics

such work can be done." Somehow sensing my esoteric bent, she commented

that Thor Heyerdahl had dispatched wild speculation about how the huge

stone statues on Easter Island were put in place when he re-enacted the

work by carving, moving, and erecting one.

-

- Being alone, and wanting a photograph taken of myself

in Leedskalnin's workshop, I did not want to be argumentative. Smiling,

I handed her the camera and did not point out that Heyerdahl, unlike Leedskalnin,

had an ample supply of willing and healthy natives. They provided sufficient

manpower to satisfy the physical requirements for conventionally moving

such large weights, even on rollers, and cantilevering them into an upright

position. Heyerdahl was an energetic man, but, using those methods, he

could not have done it alone. Moreover, Heyerdahl merely demonstrated that

the job could be done using one particular method. Anyone who has worked

in manufacturing knows that there are many ways of doing things. To devise

a means to perform a given work and present it as the only way that such

work could be done gives little credit to those who either might know of

a better way or might look for a better method-and succeed in finding one.

-

- When analyzing ancient engineering feats, and being faced

with explaining technically difficult tasks, Egyptologists and archaeologists

typically throw in more time and more people using primitive, simple tools

and manpower. Unlike those conventional arguments regarding ancient civilizations,

in the case of Ed Leedskalnin we cannot impose the view that the work was

done employing masses of people, for it is well documented that Leedskalnin

worked alone.

-

- Egyptologists claim to "know" how the Great

Pyramid was built. To prove it, stones no heavier than two and one-half

tons were hefted into place using a gang of workers, straining on ropes.

Leedskalnin claimed to "know" how the Great Pyramid was built,

and to prove it he moved a thirty-ton and other monolithic blocks of coral

to build his castle. It is too bad the cameras were not on Leedskalnin

as they were on the NOVA experiment. I believe that Leedskalnin's feat

is more illustrative of the pyramid builders' methods. While I enjoyed

This Old Pyramid, I was not too impressed with the results. After a tremendous

amount of effort using modern tools and equipment, the crew managed to

move a few blocks into place using only manpower. After recently talking

to Roger Hopkins, who was the mason in charge of the construction of the

pyramid for the NOVA film, I have a lot more respect for the effort and

knowledge that he put into it under extremely arduous conditions. Hopkins

is very straightforward and an honest craftsman who specializes in working

in granite. Like me, he is convinced that the ancients were using state-of-the-art

equipment to perform this work. But the equipment and techniques Leedskalnin

used, I would suggest, goes beyond what we know as state-of-the-art. What

technique did he use? Can we regain the knowledge he took with him to his

grave? What follows is a speculation about the techniques that Leedskalnin

may have used. It follows his basic premise regarding the nature of electricity

and magnetism and leads to a conclusion that, I believe, has some semblance

of logic. This speculation followed some basic rules for brainstorming-those

that follow and that might eventually reveal the secret-should do the same.

First, there is no such thing as a stupid idea, and, second, what we have

been taught about the subject may not necessarily apply when seeking and,

hopefully, finding a real solution.

-

- A paradigm shift in my perception of "antigravity"

occurred when my coworker, Steven Defenbaugh, and I were discussing the

subject with Judd Peck, the CEO of the company for which we both work.

Peck asked the simple question, "What is antigravity?" In an

attempt to define it I had to say, "A means by which objects can be

lifted, overcoming the gravitational pull of the Earth." As I spoke,

it occurred to me that we were already applying antigravitational techniques

in our everyday life. When we get out of bed in the morning, we employ

antigravity just by standing up. An airplane, a rocket, a forklift truck,

and an elevator are technologies devised to overcome the effects of gravity.

Even a car rolling along on its wheels is an antigravity device. Without

the wheels and a propulsion system, it would be just dead weight.

-

- I realized that I had been laboring under the assumption

that in order to create an antigravity device, gravity should be a known

and fully understood phenomenon and that, through the application of technology,

out-of-phase gravity waves would have to be created in such a manner as

to neutralize it. As any physicist will tell you, the nature of gravity

still eludes us, as does the ability to produce interference gravity waves.

So what if there is no such thing as gravity? What if the natural forces

we already know about are sufficient to explain the noted phenomenon we

have labeled as gravity? If, as Leedskalnin claimed, all matter consists

of individual magnets, wouldn't the known properties of a magnet be sufficient?

We know that like poles repel, and unlike poles attract. We also know that

we can suspend one magnet above another as long as we do not allow either

of them to flip over so that the opposite poles attract each other. Magnets

seek to attract and, left to themselves, will align their opposite poles

to each other. A mag-lev train is a good example of an antigravity device

employing magnets.

-

- The Earth, having the properties of a large magnet, generates

streams of magnetic energy that follow lines of force. These lines of force

have been noted for centuries. If we assume, as Leedskalnin did, that all

objects consist of individual magnets, we also can assume that an attraction

exists between these objects due to the inherent nature of a magnet seeking

to align its opposite pole to another. Perhaps Leedskalnin's means of working

with the Earth's gravitational pull was nothing more complicated than devising

a means by which the alignment of magnetic elements within his coral blocks

was adjusted to face the streams of individual magnets he claimed are streaming

from the Earth with a like repelling pole.

-

- A well-known method for creating magnetism in an iron

bar is to align the bar with the Earth's magnetic field and strike the

bar with a hammer. This blow vibrates the atoms in the bar and allows them

to be influenced by the Earth's magnetic field. The result is that when

the vibration stops, a significant number of the atoms have aligned themselves

within this magnetic field.

-

- Was this the method that Leedskalnin was using? It is

a simple concept, and when I observed the devices in Leedskalnin's workshop,

I could easily imagine the application of vibration and electromagnetism.

His flywheel for creating electricity remains motionless, for the most

part, until inquisitive tourists like me come along and give it a spin.

After giving it a few revolutions, I realized that something was missing.

The narrative I heard, while browsing around the castle, described Leedskalnin

as using this device to create electricity to power his electric lightbulbs.

It was claimed that Leedskalnin did not have electricity, but I could not

imagine this device being a useful and continuing source of power, considering

Leedskalnin used only his right arm to turn the wheel. On closer examination

of the piece, I found that the whole assembly was actually an old four-cylinder

crankcase. His flywheel was mounted on the front end of the crankshaft

and consisted of bar magnets that were sandwiched between two plates-the

upper plate being a ring gear. To give it weight and to solidify the entire

assembly, Leedskalnin had encased the bar magnets with cement. It then

occurred to me that the photo of Leedskalnin with his hand on the crank

handle-which is attached to the end of the shaft-might not accurately represent

his entire operation. It is possible that Leedskalnin was using the crank

handle to start a reciprocating engine, now missing, which attached to

one of the throws on the crankshaft. He would then be able to walk away

and leave his flywheel running.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- I was now mystified. I had developed a notion that the

bars attached to the flywheel were actually being used to develop vibration

in the piece Leedskalnin was trying to lift. This idea did not make sense

considering the type of material, size, and weight of the entire assembly.

The crankcase was firmly attached to the coral block in his workshop, and

even if it were not attached, it would be quite a feat to keep moving it

about. There was one factor I needed to check out, though, before I headed

back to Illinois. I had tested the bar magnet with a pocketknife. The knife

was attracted to each bar. I needed to know, conclusively, the arrangement

of the poles in the wheel-to see, indeed, whether the assembly was capable

of creating electricity.

-

- I headed for the nearest strip mall to look for a hardware

store so that I could buy a bar magnet. The first one had just what I needed-and

for only $1.75. Feeling rather pleased, I returned to Coral Castle.

-

- Once there, I headed back into Leedskalnin's workshop

and put the magnet to the test. I held it a short distance away from the

spokes of the flywheel while giving it a spin. Sure enough, I found out

what I had come for. The magnet pushed and pulled in my grasp as the wheel

rotated. Looking around the space, I gazed at a jumble of various devices,

lying, hanging, and leaning about the room. There were radio tuners, bottles

with copper wire wrapped around them, spools of copper wire, and other

various and sundry plastic and metal pieces that looked as if they had

fallen out of an old radio set. Leedskalnin's workshop also contained chains,

block and tackle, and other items that one might find lying around a junk-yard.

Some items were missing, though. Photographs of Leedskalnin at work show

three tripods-made of telephone poles-that have boxes attached to the top.

These objects, however, are not to be found at Coral Castle. What is striking

in the photograph is that the block of coral being moved is seen off to

the side of the tripod. Perhaps Leedskalnin had moved the tripod after

raising the block out of the bedrock. Another interesting observation is

that the block and tackle that can be found inside his workshop is nowhere

to be seen in this photograph. There are spools of copper wire in his workshop,

and two wrappings of copper wire hanging from nails in the wall. One was

round copper and the other flat copper. In a narrative that visitors can

hear at various recording stations around the compound, it is stated that

at one time Leedskalnin had a grid of copper wire suspended in the air.

Looking at the photograph again, one can see that there is a cable draped

around the tripod and running down to the ground. Perhaps the arrangement

of tripods was more related to the suspension of his copper grid than to

the suspension of block and tackle.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- If I were to try to replicate Leedskalnin's feat, I would

begin with the premise that he was using his flywheel to generate a single-frequency

tunable radio signal. The box at the top of the tripod would contain the

radio receiver (there are several tuners in Leedskalnin's workshop), and

the cable coming from the box would be attached to a speaker that emitted

sound to vibrate the coral rock at its resonant frequency. With the atoms

in the coral vibrating (like those in an iron bar), I would then attempt

to flip their magnetic poles-which are naturally in an attraction orientation

with the Earth-using an electromagnetic field.

-

- Although today we stand in amazement before ancient megalithic

sites that were built employing huge stones, if we had Leedskalnin's technique

for lifting huge stones, it would make sense to us that the ancient masons

might make their building blocks as large as possible. Very simply, it

would be more economical to build in that manner. If we had a need to fill

a five-foot cube, the energy and time required to cut smaller blocks would

be much greater than what would be required to cut a large one.

-

- I have no doubt that Leedskalnin told the truth when

he said he knew the secrets of the ancient Egyptians. Unlike those who

have sought publicity for their own inadequate, although politically correct,

theories, he proved his theory through his actions. I believe, also, that

we can rediscover his techniques and put them to use for the benefit of

humankind. Edward Leedskalnin, right or wrong, had a little bit of a problem

with trust-but this modus operandi was not unusual for a craftsperson of

his day. Proprietary techniques without patent disclosure assure continued

employment; therefore, it was perfectly normal that he would protect his

secret from prying eyes that might steal and profit from it. I believe

there are enough pieces of the puzzle in Leedskalnin's workshop to allow

us to put them together and replicate his technique. It has been done once

(sorry, twice)! and I am sure that it can be done again.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

|