Melon-Headed

Dolphins Died |

By

Yoichi Shimatsu |

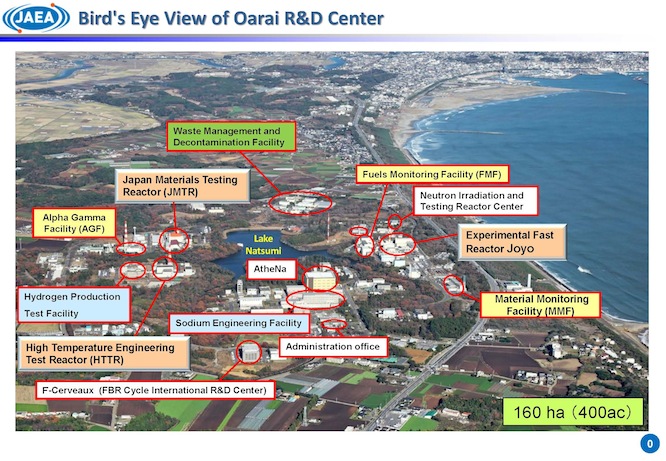

The mass stranding of more than 150 melon-headed whales on the beaches of Ibaraki, a coastal prefecture neighboring Tokyo, has been attributed to underwater seismic rumblings or, alternatively, described as a biological mystery. Neither an acute sensitivity to earthquakes nor an undetected virus were the probable cause of death, not when a simpler explanation is so obvious. The beaches at Hokota town are located between the Oarai atomic research complex, site of the Joyo plutonium fast-breeder reactor, and the Tokaimura atomic energy plant, and down-current from the Fukushima No.1 and No.2 nuclear plants. The melon heads, which are also called electra dolphins, must have died from the harmful effects of radiation exposure. The seismic-premonition theory is based, wrongly, on the coincidence of an earlier stranding of a pod of 50 dolphins of the same species at nearby Oarai just six days before the massive Tohoku Earthquake of March 11, 2011. Oarai is 90 kilometers from the quake’s epicenter deep down in the Japan Trough, so the more probable cause for that beaching lies closer to home. On February 11 of that same year, the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) ordered the emergency shut-down of its experimental high-temperature nuclear reactor at Oarai without citing a specific cause of system failure. Even though the test reactor is cooled by helium, waste heat still has to be exchanged with water, opening a channel for nuclear releases into the sea after any rupture in the cooling system. Other research facilities at Oarai include Japan’s third plutonium-fueled breeder reactor, Joyo, and a nuclear-decontamination program. JAEA was the lead agency for decontamination techniques after the Fukushima disaster. Its preferred method is the spraying of water to wash radioactive particles downstream and out to sea. Oceanic releases were undoubtedly tested over the years at Oarai at great risk to marine life. The JAEA, a branch of the Ministry of Education, Sports, Culture, Science and Technology (MEXT), is a government institute that operates beyond the reach of regulators and without parliamentary oversight. The underlying reason for such legal immunity is its premier role in directing Japan’s covert nuclear-weapons program. Besides accumulation of the nation’s plutonium stockpile, the atomic agency also supervises tritium recovery inside civilian commercial reactors. Tritium, neutron-enriched heavy water, is used to trigger plutonium payloads of thermonuclear bombs.

Six days before the 311 disaster at nearby Fukushima, 50 Melon-headed whales were stranded on the beaches at Oarai, Ibaraki Prefecture, near this nuclear complex operated by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency. A month earlier, on February 11, 2011, the HTTR reactor (shown on the lower left) was shut down in an emergency, indicating a major radioactive leak that may have contaminated the seawater. Joyo (to the far right) is a plutonium fast-breeder reactor. The recent dolphin beachings occurred between this facility and the Tokaimura nuclear-power plant to the north. Contaminated water from Fukushima No.1 plant flows less than a kilometer offshore and irradiates the shoreline. (photo-map from the website of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency) Japan’s Bomb Makers JAEA’s top-secret weapons program requires the subordination of regional utilities, including Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) and Tohoku Electric Power. The illegality of these military-related activities are behind the past four years of cover-ups at the Fukushima and Onagawa nuclear plants. Official denial is also behind TEPCO’s all-clear report on radiation levels along the Ibaraki coast. Readings taken at shoreline monitoring stations are rated “lower than the minimum level of detection”. This claim of seawater safety is challenged by reports from scuba divers of massive kill-offs of shellfish along the narrow coastal shelf. My own shoreline surveys done in autumn 2011, summer 2012 and autumn 2013 indicated significant radioactive bioaccumulation in seaweed, shellfish, fish carcasses and squid cartilage found in local tide pools. Identical Symptoms at San Onofre Veterinary autopsies on 17 beached melon-headed whales retrieved at Hokota were done by a 30-member team of marine mammal experts with the Japan National Museum of Nature and Science, headquartered in Tokyo’s Ueno Park with research facilities at Tsukuba University. The initial findings include: extreme blood loss in the lungs, a condition described in medical terms as ischemia; no presence of cancer or infections; and a surprising lack of decay. The pure-white lung tissue, without a drop of blood content, had never been seen before by those veteran researchers. Ischemia is a rare disorder in humans mostly concentrated in Central Europe following the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. The findings in the melon-headed whales is therefore disturbing to say the least for residents in the greater Fukushima disaster zone, which extends into parts of Tokyo. The symptoms found in the Hokota dolphins are identical to the findings from my field research on an adult female sea lion killed by radioactive wastewater releases. In that 2013 field study of marine mammals and birds in the environs of the Southern California Edison nuclear plant at San Onofre, I found the deceased sea lion in front of the plant’s twin domes. In an article for this online news site (rense.com/general95/sanofre.html), I released photos of dosimeter readings taken inside the body cavity, which indicated catastrophic heart failure. Cesium ingestion is known to cause heart palpitations and atrophy of coronary muscles, resulting in a drop in blood pressure. The specimen at San Onofre did not emit any odor from its gut or internal organs. The softness of its organs, which were unaffected by decomposition except for the darkened heart muscle, indicated an aseptic state of radioactive “mummification”. Radiation apparently destroyed bacteria and other pathogens. Her stomach and intestines were absent of any remnant food, meaning the sea lion had suffered extreme starvation for weeks.despite an abundance of mackerel and squid in the Catalina Channel. My conclusion was that diminished blood flow had weakened the predator to a point where she lacked the strength to pursue and catch fish. A question that arises is: Where did the blood go? Presumably, the weakening heart contractions trapped blood inside a gradually swelling aorta. When the heart valves and arteries finally burst, the blood escaped into the body cavity, as evidenced in dark maroon discoloration between the ribs and belly. Marine animals differ from land creatures in the lower levels of radiation detected inside their flesh. Sea creatures are constantly immersed in a low-level radioactive medium. Most of the radioactive salts do not accumulate in their flesh yet nonetheless have a lethal effect due to persistent gamma-ray exposure. Ingestion patterns are also much different from land species due to the higher water content of a marine diet. Low radiation levels in a marine environment can lead to internal organ failure and resultant loss of mobility. Two nuclear sites, more than 8,000 kilometers apart, were the scenes of identical findings in two different types of marine mammals. The logical conclusion is that other oceanic species are also suffering extreme physical effects from nuclear releases into the oceans, leading toward a series of extinction events. Propaganda in the Guise of Education The Nature and Science Museum, like the atomic research agency, is under the authority of the pro-nuclear Ministry of Education. Its bureaucrats hew to pseudoscience theories trumpeting Japanese uniqueness and superiority, contrary to historical facts. The ministry is a bastion of ultra-nationalist propagandists sworn to overthrow the pacifist Constitution, whitewash past war crimes and unleash the Japanese military from civilian authority. Education policy in Japan is, in short, a national disgrace in the service of aggression, which is partially contested by a beleaguered corps of teachers dedicated to historical truth and moral accountability. If the bogus “scientific” research on Antarctic whaling vessels serves as any indicator, censorship from MEXT poses an impediment to an accurate autopsy report on the stranded melon-headed whales. The researchers at the Nature and Science Museum have a courageous record for their studies on controversial toxicity issues including the effects of Agent Orange on Southeast Asian marine mammals and industrial pollution harmful to oceanic invertebrates. Bucking the totalitarian system is difficult for Japanese researchers, so it is therefore high time for the scientific community worldwide to draw a line in the sand against the nuclear lobby. Stand together for truth or perish in falsehood. Marine biology is a sensitive field in Japan due to the personal legacy of Emperor Hirohito, who chose the quiet pursuit of sea-life research after his disastrous wartime experience. For many observers near the end of his Showa Era, scenes of the elderly emperor probing tidal pools with trousers rolled up to his knees was a manifestation of regret and penance arising from his heartfelt appreciation of life so precious in contrast with military vainglory. These opposed viewpoints are again at odds, as the bureaucrats and militarist politicians dishonor the final wishes of the late emperor. Tragic End for Playful Creatures The melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra or electra dolphin) is a tropical species in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and Ibaraki is their northernmost destination. Riding the fast current of the Kuroshio northward, the electra dolphins, which are slightly longer than humans, enjoy skipping over the waves like puppies bounding across a meadow. At Choshi Point, east of Tokyo, the Kuroshio collides with the Oyashio, which flows down from the Arctic. Merging together, these streams form the east-moving North Pacific Current. The turbulent mixing of cold and warm waters nourishes an abundance of algae and plankton for schools of squid, the main feedstock for the melon heads. The squid cartilage is especially harmful to dolphins as a bioaccumulator of radioactive salts, including strontium. Since the chill temperatures north of Choshi Point are not to their liking, the playful creatures dawdle in the sunny shallows along the Ibaraki bight. The cruelty of nuclear energy, though unintended by its creators, is demonstrated in how the melon-headed whales are lured to their destruction. The siren songs come from the outflow of warm wastewater from nuclear facilities. There, in the 23-km space between Hokota and Oarai, the irradiated hot waters beckon these unsuspecting marine mammals to bask like tourists in an onsen or hot springs. That curving shore is a perfect death trap. Since the melon-headed whales are not on the endangered species list, why should anyone such as an industrialist whose factories rely on nuclear power or the investment banker who feasts on dividends from utilities care about these spirits from the deep? Remember to ask that question on the next summer vacation when watching over the kids at the beach. Yoichi Shimatsu, former general editor of The Japan Times Weekly, is a science journalist and environmental consultant who has conducted radiation studies inside the Fukushima exclusion zone since spring 2011. |

| Donate to Rense.com Support Free And Honest Journalism At Rense.com | Subscribe To RenseRadio! Enormous Online Archives, MP3s, Streaming Audio Files, Highest Quality Live Programs |