- "Expose the victorious Allies in their treatment

of the enemy at peace, for in most cases it was not the criminals who were

raped, starved, tortured or bludgeoned to death but women, children and

old men."

-

- Part I

-

- Those who honestly chronicle human events, present or

past, are a rare and honorable breed. We should certainly ennoble them

within the pantheon of our earthly gods. As we do so, we will no doubt

include those who, not out of alienation against the West or the United

States or its people but out of a thirst for truth, are bringing to light

the awful events that followed in the wake of World War II (as well as

the enormities that were committed as part of the way in which the war

was fought against civilian populations, although that is a subject we

won't be exploring here).

-

- That war has been known among Americans as "the

good war," and those who fought it as "the greatest generation."

But now, slowly, we are hit by the realities so commonplace to a complex

human existence: there was much that was not good, and along with the self-sacrifice

and high intentions there was much that was venal and brutal. These realities

are coming to the surface because there are some scholars, at least, who

are aware that an ocean of wartime propaganda spawns a myth that continues

for several decades and who have a commitment to truth that overrides the

many inducements to conform to the myth.

-

- This article began as a simple review of Giles MacDonogh's

book that is identified above. His book is largely of the myth-breaking

sort I have just praised. Because, however, there is valuable additional

material that I am loath to leave unmentioned, I have expanded it to include

other information and authors, although leaving it primarily a review of

After the Reich.

-

- MacDonogh's is a puzzling book, both brave and craven,

mostly (but not entirely) worthy of the high praise we must give to incorruptible

scholars. As we have noted, the American public has long thought of the

Allied effort in World War II as a "great crusade" that pitted

good and decency against Nazi evil. Even after all these years, it is likely

that the last thing the public wants to learn is that vast and unspeakable

wrongs were committed by both the Western Allies and the Soviet Union during

the war and its aftermath. It flies in the face of that reluctance for

MacDonogh to tell "the brutal history" at great length.

-

- That willingness is commendable for its intellectual

bravery. In light of it, it is puzzling that even as he does so he puts

a gloss over that history, in effect continuing in part a cover-up of historic

proportions that has been fixed in place by the overhang of wartime propaganda

for almost two-thirds of a century.

-

- The great value of his book thus cannot be found in its

completeness or its strict candor, but rather in its providing something

of a bridge-albeit quite an extensive one-that can start conscientious

readers toward further study of an immensely important subject.

-

- For this article, it will be valuable to begin by summarizing

the history MacDonogh relates (and to add somewhat to it). It is only after

doing this that we will discuss what MacDonogh obscures. All of this will

then lead to some concluding reflections.

-

- In his Preface, MacDonogh says his purpose is to "expose

the victorious Allies in their treatment of the enemy at peace, for in

most cases it was not the criminals who were raped, starved, tortured or

bludgeoned to death but women, children and old men." Although this

suggests the tone of the book will be one of outrage, the narrative is

in the main informative rather than polemical.

-

- MacDonogh's scholarly background includes several books

of German and French history and biography (as well as four books on wine).

-

- The expulsions (today called "ethnic cleansing").

-

- At the end of the war, MacDonogh tells us, "as many

as 16.5 million Germans were driven from their homes." 9.3 million

were expelled from the eastern portion of Germany, which was made a part

of Poland.

-

- (Both the eastern and western boundaries of Poland were

drastically shifted westward by agreement of the allies, with Poland taking

an important part of Germany and the Soviet Union taking eastern Poland.)

The other 7.2 million were forced from their ancestral homes in Central

Europe where they had lived for generations.

-

- This mass expulsion was settled upon in the Potsdam Agreement

in mid-1945, although the Agreement did make it explicit that the ethnic

cleansing was to take place "in the most humane manner possible."

Churchill was among those who supported it as conducive "to lasting

peace."

-

- In fact, the process was so inhumane that it amounted

to one of history's great atrocities. MacDonogh reports that "some

two and a quarter million would die during the expulsions." This is

at the lower end of such estimates, which range from 2.1 million to 6.0

million, if we take only the expellees into account. Konrad Adenauer, very

much a friend of the West, found himself able to say that among those expelled

"six million GermansS are dead, gone."[1] We will be seeing MacDonogh's

account of the starvation and exposure to extreme cold to which the post-war

population of Germany was subject, and it is worth mentioning at this point

(even though it goes beyond the expulsions) that the historian James Bacque

says that "the comparison of the censuses has shown us that some 5.7

million people disappeared inside Germany between October 1946 [a year

and a half after the war ended] and September 1950S."[2]

-

- What MacDonogh calls "the greatest maritime tragedy

of all time" occurred when the ship the Wilhelm Gustloff, carrying

Germans from Danzig in January 1945, was sunk with "anything up to

9,000 people,S many of them children." In mid-1946, "pictures

show some of the 586,000 Bohemian Germans packed in box cars like sardines."

At another point MacDonogh tells how "the refugees were often packed

so tightly that they could not move to defecate and emerged from the trucks

covered with excrement. Many were dead on arrival." [This calls to

mind the scenes described so vividly in Volume I of Solzhenitsyn's The

Gulag Archipelago.] In Silesia, "streams of civilians were forced

from their homes at gunpoint." A priest estimated that a quarter of

the German population of one Lower Silesian town killed itself, as entire

families committed suicide together.

-

- The condition of the German population--starvation and

extreme cold. Germans refer to 1947 as Hungerjahr, the "year of hunger,"

but MacDonogh says that "even by the winter of 1948 the situation

had not been remedied." People ate dogs, cats, rats, frogs, snails,

nettles, acorns, dandelion roots and wild mushrooms in a feverish effort

to survive. In 1946, the calories provided in the U.S. Zone of Germany

dropped to 1,313 by March 18 from the mere 1,550 provided earlier. Victor

Gollancz, a British and Jewish author and publisher, objected that "we

are starving the Germans."[3] This is similar to the statement made

by Senator Homer Capehart of Indiana in a speech to the U. S. Senate on

February 5, 1946: "For nine months now this administration has been

carrying on a deliberate policy of mass starvationS."[4] MacDonogh

tells us that the Red Cross, Quakers, Mennonites and others wanted to bring

in food, but "in the winter of 1945 donations were returned with the

recommendation that they be used in other war-torn parts of Europe."

In the American zone of Berlin, "it was American policy that nothing

should be given away and everything should be thrown away. So those German

women who worked for the Americans were fantastically well fed, but could

take nothing home to their families or children." Bacque says "foreign

relief agencies were prevented from sending food from abroad; Red Cross

food trains were sent back to Switzerland; all foreign governments were

denied permission to send food to German civilians; fertilizer production

was sharply reducedS The fishing fleet was kept in port while people starved."[5]

-

- Under the Russian occupation of East Prussia, MacDonogh

sees "striking similarities" to Stalin's "deliberate starvation

of the Ukrainian kulaks in the early 1930s." As in the Ukraine, "cases

of cannibalism were reported, with people eating the flesh of their dead

children."

-

- The suffering from extreme cold mixed with the starvation

to create misery and a heavy death toll. Even though the winter in 1945-6

was a normal one, "the terrible lack of coal and food was acutely

felt." Abnormally cold winters struck in 1946-7 ("possibly the

coldest in living memory") and 1948-9. In Berlin alone, 60,000 people

were thought to have died within the first ten months after the end of

the war; and "the following winter killed off an estimated 12,000

more." People lived in holes among the ruins, and "some Germans-particularly

refugees from the east-were virtually naked."

-

- In his book Gruesome Harvest: The Allies' Postwar War

Against The German People, Ralph Franklin Keeling cites a quote from a

"noted German pastor": "Thousands of bodies are hanging

from trees in the woods around Berlin and nobody bothers to cut them down.

- Thousands of corpses are carried into the sea by the

Oder and Elbe Rivers-one doesn't notice it any longer. Thousands and thousands

are starving in the highwaysS Children roam the highways aloneS."[6]

-

-

- In his The German Expellees: Victims in War and Peace,

Alfred-Maurice de Zayas told how in Yugoslavia Marshal Tito used camps

as extermination centers to starve Germans.[7]

-

- Mass rape-to which one must add the "voluntary sex"

obtained from starving women.

-

- The onslaught of rape by invading Russian forces is,

of course, infamous. In the Russian zone of Austria, "rape was part

of daily life until 1947 and many women were riddled with VD and had no

means to cure it." MacDonogh tells us that "conservative estimates

place the number of Berlin women raped at 20,000." When the British

arrived in Berlin, "officers later recalled the shock of seeing the

lakes in the prosperous west filled with the corpses of women who had committed

suicide after being raped." The age of the victim made little difference,

with those raped ranging from 12 to 75. Nurses and nuns were among the

victims (some as many as fifty times). "The Russians were particularly

hard on the nobles, setting fire to their manor houses and raping or killing

the inhabitants." Although "most of the unwanted Russian children

were aborted," MacDonogh says "it is estimated that between 150,000

and 200,000 'Russian babies' survived." The Russians raped wherever

they went, so that it wasn't just German women who were raped, but also

women of Hungary, Bulgaria, the Ukraine, and Yugoslavia even though it

was on the same side.

-

- There was an official policy against rape, but it was

so commonly ignored that "it was only in 1949 that Russian soldiers

were presented with any real deterrent." Until then, "they were

egged on by [Ilya] Ehrenburg and other Soviet propagandists who saw rape

as an expression of hatred."

-

- Although there was a "widespread incidence of rape

by American soldiers," there was an enforced military policy against

it, with "a number of American servicemen executed" for it. Criminal

charges brought for rape "rose steadily" during the final months

of the war, but declined sharply thereafter. What did continue was arguably

almost as bad: the sexual exploitation of starving women who "voluntarily"

sold sexual services for food. In Gruesome Harvest, Keeling quotes from

an article in the Christian Century for December 5, 1945: "The American

provost marshalS said that rape represents no problem for the military

police because 'a bit of food, a bar of chocolate, or a bar of soap seems

to make rape unnecessary.'"[8]

-

- The extent of this is shown by the figure MacDonogh provides

of an "estimated 94,000 Besatzungskinder or 'occupation children'

[who] were born in the American zone." He says that in 1945-6 "many

female children resorted to prostitution to survive. Boys, too, performed

a service for Allied soldiers."

-

-

-

-

- Keeling, writing for the 1947 publication of his book

[which explains his use of the present tense], said there was "an

upsurge in venereal diseases which has reached epidemic proportions,"

and went on to say that "a large proportion of the contamination has

originated with colored American troops which we have stationed in great

numbers in Germany and among whom the rate of venereal infection is many

times greater than among white troops." In July 1946, he says, the

annual rate of infection for white soldiers was 19%, for black troops 77.1%.

He reiterated the point we are making here when he pointed to "the

close connection between the venereal disease rate and availability of

food."[9]

-

-

-

-

-

-

- If MacDonogh mentions rape by British soldiers, it has

escaped me. He does tell, however, of rape by Poles, the French, Tito's

partisans, and displaced persons. In Danzig, "the Poles behaved as

badly as the RussiansS It was the Poles who liberated the town of Teschen

in the north [of Czechoslovakia] on 10 May. For five days they raped, looted,

torched and killed." He writes of "French soldiers' behaviour

in Stuttgart, where perhaps 3,000 women and eight men were raped,"

says "a further 500 women [were] raped in Vaihingen," and reports

"three days of killing, plunder, arson and rape" in Freundenstadt.

Of the displaced persons, he says that "there were around two million

POWs and forced labourers from Russia who had formed into gangs and robbed

and raped all over central Europe."

-

- =====

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Part II

-

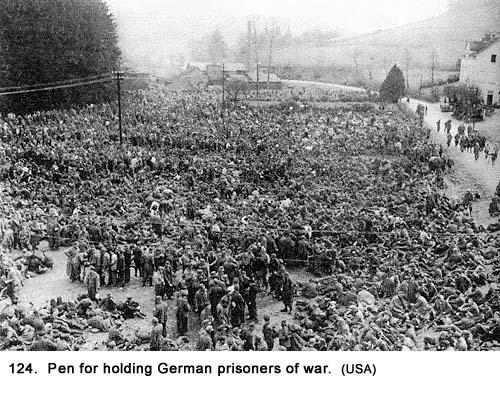

- Treatment of the prisoners of war. In all, there were

approximately eleven million German prisoners of war. One and a half million

of these never returned home. MacDonogh expresses an appropriate outrage

here: "To treat them with so little care that a million and a half

died was scandalous."

-

- The Red Cross had no role vis a vis those held by the

Russians, since the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention.

MacDonogh says the Russians made no distinction between German civilians

and prisoners of war, although we know that a KGB report does sort them

out for deaths and other purposes. At war's end, they held approximately

four to five million within Russia (and here, again, the KGB archives are

worth consulting, as historian James Bacque has done; they show a figure

of 2,389,560). Large numbers were held for over ten years, being sent back

to Germany only after Konrad Adenauer's visit to Moscow in 1956. Nevertheless,

in 1979-34 years after the end of the war!-"there were believed to

be 72,000 prisoners still alive in-chiefly Russian-custody." Some

90,000 German soldiers were captured at Stalingrad, but only 5,000 made

it home.

-

-

-

-

-

- The Americans made a distinction between the 4.2 million

soldiers captured during the war, who were entitled to the shelter and

subsistence called for by the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and the 3.4

million captured in the West at its end. MacDonogh says the latter were

classified as "Surrendered Enemy Persons" (SEPs) or as "Disarmed

Enemy Persons" (DEPs), and were denied the protections of the Conventions.

He doesn't give a total figure for those who died in American custody,

saying "it is not clear how many German soldiers died of starvation."

He tells, however, of several situations: "The most notorious American

POW camps were the so-called Rheinwiesenlager." Here, the Americans

allowed "anything up to 40,000 German soldiers to die from hunger

and neglect in the muddy flats of the Rhine." He says "any attempt

to feed the prisoners by the German civilian population was punishable

by death." Although the Red Cross was empowered to inspect, "the

barbed wire surrounding the SEPs and DEPs was impenetrable."

-

- Elsewhere, at "the Pioneers' Barracks in WormsS

there were 30,000-40,000 prisoners sitting in the courtyard, jostling for

space. With no protection from the rain they froze." The prisoners

were starved at Langwasser, and at a "notorious camp" at Zuffenhausen

where "for months lunch was turnip soup, with half a potato for dinner."

-

-

-

-

-

- It would be a mistake to think that a world food shortage

caused the United States to be unable to feed its prisoners. Bacque writes

that "Captain Lee Berwick of the 424th Infantry who commanded the

guard towers at Camp BretzenheimS told me, 'Food was piled up all round

the camp fence.' Prisoners there saw crates piled up 'as high as bungalows.'"[10]

-

- What MacDonogh tells us about Britain's treatment of

German POWs seems conflicting. It had 391,880 prisoners working in Britain

in 1946, and a total of 600 camps there in 1948. He says "the regime

was not so hard, and in terms of percentages the number of men who died

in British custody is strikingly low compared to the other Allies."

Elsewhere, however, he tells how "the British could evade [the Geneva

Convention's stipulation]S that they provide 2,000 to 3,000 calories a

day," so that "for most of the time levels fell below 1,500 calories."

The British had a camp in Belgium that "was meant to be particularly

grueling." There, "conditions for the 130,000 prisoners were

reported to be 'not much better than Belsen'S When the camp was inspected

in April 1947 there were found to be just four functioning lightbulbsSthere

was no fuel, no straw mattresses and no food apart from 'water soup.'"

-

- A Reuters report in December 2005 adds an important dimension:

"Britain ran a secret prison in Germany for two years after the end

of World War II where inmates including Nazi party members were tortured

and starved to death, the Guardian says.

-

- Citing Foreign Office files that were opened after a

request under the Freedom of Information Act, the newspaper says Britain

had held men and woman [sic] at a prison in Bad Nenndorf until July 1947S

'Threats to execute prisoners, or to arrest, torture and murder their wives

and children were considered "perfectly proper" on the grounds

that such threats were never carried out,' the paper reports."[11]

-

- The French wanted German labor to help rebuild the country,

and for this purpose the British and Americans transferred about a million

German soldiers to them. MacDonogh says "their treatment was particularly

brutal." Not long after the war, according to the Red Cross, 200,000

of the prisoners were starving.

- We are told of a camp "in the Sarthe [where] prisoners

had to survive on 900 calories a day."

-

- The stripping of the German economy. Allied leaders disagreed

among themselves about the Morgenthau Plan to strip Germany bare of industrial

assets and turn it into an agrarian country. The opposition of some and

hesitation of others did not, however, prevent a de facto implementation

of the plan. By the time the confiscation was ended, Germany was largely

bereft of productive assets.

-

- MacDonogh says that under the Russians "Berlin lost

around 85 percent of its industrial capacity." Every machine was taken

from Vienna. The ships were taken from the Danube, and "one Soviet

priority was the seizure of any important works of art found in the capital

[Vienna]. This was a fully planned operation." But "worse than

the full-scale removal of the industrial base of the land was the abduction

of men and women to develop industry in the Soviet Union."

-

-

-

-

-

- Under the Americans, the dismantling of industrial sites

continued until General Lucius Clay stopped it a year after war's end.

Until Clay acted, Clause 6 of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Order 1067 embodied

the Morgenthau Plan. MacDonogh says that where "American official

theft was carried out on a massive scale" was in "seizing scientists

and scientific equipment."

-

- The British took much for themselves and passed other

industrial property on to "client states" such as Greece and

Yugoslavia. The British royal family received Goering's yacht, and the

British zone of Germany was stripped of "plants that might later offer

competition with British industries." MacDonogh says "the BritishS

had their own brand of organized theft in [something called] T-Force, which

sought to glean any industrial wizardryS."

-

- For their part, the French asserted "the right to

plunder." "The FrenchS made no bones about pocketing a chlorine

business in Rheinfelden, a viscose business in Rottweil, the Preussag mines

or the chemicals groups Rhodia,"S and much more.

-

-

-

- German Industrial Area After Bombing, before

Plundering

-

-

- If the Plan had been fully implemented over a longer

period of time, the effects would have been calamitous. Keeling, in Gruesome

Harvest, says that by seeking "the permanent destruction of Germany's

industrial heartland" it would have had as an "ineluctable consequenceS

the death through starvation and disease of millions and tens of millions

of Germans."[12]

-

- The forced repatriation of Russians to Stalin. MacDonogh's

book limits itself to the Allied occupation, but there are, of course,

many other aspects of the aftermath of the war that deserve mention, although

here we will limit ourselves to just one of them. (MacDonogh does give

some details about it.) It is the Allied repatriation of captured Russians

to the Soviet Union. In The Secret Betrayal, Nikolai Tolstoy tells how

between 1943 and 1947, a total of 2,272,000 Russians were returned. The

Soviets harvested 2,946,000 more from the parts of Europe taken by the

Red Army. Those sent to the Soviet Union by the Western democracies included

thousands of people who were Tsarist emigres and had never lived under

the Soviet regime. Tolstoy says that even though there were many who did

want to return to Russia (while many others desperately did not, and were

sent back, in effect, kicking and screaming), they were uniformly brutalized,

executed, raped or made into slaves. Some of the repatriates were Russians

who had volunteered to fight for Germany against the Soviet Union and who

were led by General Vlasov. Some were Cossacks, many of whom were not even

Soviet citizens. The violent repatriations began in August 1945. Tolstoy

recounts how deception, clubbings, bayonets, and even threats from a flame-throwing

tank were employed to force the removal.[13]

-

- Victors' justice. When the war was over, there was a

consensus among the Allies' leaders that the top Nazis should be put to

death. Some wanted immediate execution, others "a drumhead court martial."

There was an odd virtue in the insistence by the British on following "legal

forms," which is what was decided upon. The result was a series of

trials with the trappings of normal judicial proceedings, but that were

actually a travesty from the point of view of the "rule of law,"

lacking both the spirit and particulars of "due process." In

two chapters, MacDonogh gives an account of the main Nuremberg trial and

of the series of trials that continued for years afterwards. Among these,

the Americans conducted several trials in Nuremberg after the main one;

thousands of cases were brought before "denazification courts";

the German courts, after they were operational, continued the process;

and of course we know of Israel's trial and execution of Eichmann.

-

- There are many reasons to call it "victors' justice."

-

- For it to have been otherwise, a truly impartial tribunal

would have had to have been convened somewhere in the world (if such a

thing had been possible in the aftermath of a world war), and war crimes

committed by all sides prosecuted. But, of course, we know that such impartial

justice was not in contemplation. In the Nuremberg indictment, the Nazis

were charged with the mass killing of the Polish officer corps at the Katyn

Forest, a charge that was discretely (and with great intellectual and "judicial"

dishonesty) overlooked in the final judgment after it became clear to all

that the Soviet Union had done the killing.[14] Another of the many possible

examples would be that Nazi deportations were charged as both a war crime

and a crime against humanity at Nuremberg. By contrast, no one was ever

"brought to justice" for the Allies' expulsion of the millions

of Germans from their ancestral homes in central Europe.

-

- A source readers will find instructive. Because of the

credibility of its source, the account given by U.S. Air Force Major (retired)

Arthur D. Jacobs in his book The Prison Called Hohenasperg will be useful

to readers as they absorb (and assess) the information contained in MacDonogh's

book and those of the other authors referred to here. It is valuable as

a story both of American brutality and American compassion.

-

- Jacobs spent 22 years in the Air Force, retiring in 1973,

and then became a member of the faculty at Arizona State University for

another twenty years. His book tells the following personal story: His

German parents emigrated to the United States from Germany in 1928 and

1929. They had two sons born in Brooklyn (who were hence U.S. citizens),

one of them Arthur Jacobs. The boys lived their early years in Brooklyn,

attending elementary school.

- The family was taken and held for some time at Ellis

Island near the end of the war, and was then interned for seven months

at the Crystal City Internment Camp in Texas, where they were well treated.

They were "voluntarily repatriated" to Germany (after being threatened

with deportation) in October 1945, several months after Germany's surrender.

-

- When they arrived in Germany, Jacobs' mother was sent

to one camp, the father and two sons to another. The latter reached an

internment camp in Hohenasperg after a 92-hour journey locked inside a

boxcar in freezing weather with mostly women and children, fed only bread

and water, and "without heat, without blankets, and without toilets,

except for an open, stinking bucket." Jacobs himself was twelve, and

turned thirteen during his week at Hohenasperg before he was sent to another

camp at Ludwigsburg. At the Hohenasperg prison, he was placed under strict

discipline as a prisoner, and guards threatened him repeatedly with hanging

if he disobeyed.

-

- The camp at Ludwigsburg was in effect a holding center

pending release. It is informative that Jacobs tells us of the meager diet:

"At breakfast we received one glass of 'gray' milk and one slice of

black bread. There was no lunch meal." At supper, "each person

received one bowl of soup..., mostly water flavored by bouillon. There

were no second helpingsS I always had hunger pangs." While he and

his brother were at Ludwigsburg, they were forced to watch films of German

death camps.

-

- The mother, father and brothers were released from their

respective camps in mid-March 1946, and went to live with Jacobs' grandparents

in the British Zone. They weren't welcomed by Germans they met, because

"we were four more mouths to feed." Jacobs saw that "Germany

was war-torn and starving." He was befriended by an American soldier,

who got him a job with Graves Registration. He lost his job when the soldier

was transferred, and it became a struggle to "live through this starvation

period-the winter of 1946-1947." After much knocking about, he got

another job with the American Army, this time in a motor pool. An American

woman took an interest in him who knew of a ranch couple in southwest Kansas

who would bring them to America to live with them. Accordingly, Jacobs

and his brother left for the United States in October 1947. They had been

in Germany for 21 months. It was eleven years before Jacobs saw his parents

again. He went on, as we have said, to become a career officer in the U.S.

Air Force. After obtaining his MBA at Arizona State University, he became

an industrial engineer and later a member of the ASU faculty.

-

-

- Part III

- Germans

-

-

-

-

- If MacDonogh wrote all that we have reported (and more)

from his book, how can it be said that in important ways he continued the

cover-up of such horrors, a cover-up that since 1945 has consigned them

to a memory hole? This brings us to the book's deficiencies, which are

of such a nature as to give readers a lessened realization of the extent

of the atrocities and of who was responsible for them.

-

- Most egregious is MacDonogh's treatment of the work of

Canadian historian James Bacque, author of Other Losses and Crimes and

Mercies. When he refers to the first of these books, he says that Bacque

"claimed the French and Americans had killed a million POWs,"

a claim that "was called a work of 'monstrous speculation' and was

dismissed by an American historian as an 'absurd thesis.'"

-

- According to MacDonogh, "it has since been proved

that Bacque misinterpreted the words 'other losses' on Allied charts to

mean 'deaths'S." Accordingly, he speaks of "Bacque's red herring."

So greatly does he dismiss Bacque that in a section on "Further Reading"

at the end of the book, MacDonogh apparently forgets about Bacque entirely,

saying that "on the treatment of POWs there is nothing in English,

and the leading American expert-Arthur L. Smith-publishes in German."

-

- I thought it fair to ask Bacque what his response is

to MacDonogh's dismissal. Bacque replied that "the word speculation

describes my critics well, because it is they who have not been in all

the relevant archives and who have not interviewed the thousands of survivors

who have written to newspapers, TV journalists and other authors about

their near-death experiences in the camps of the Americans, French and

Russians."

-

- Far from admitting that he had misinterpreted the category

of "Other Losses," Bacque says that "the meaning of the

termS was explained to me by Colonel Philip S. Lauben, United States Army,

who was in charge of movements of prisoners for SHAEF in 1945. I have the

interview on tape and Lauben's signature on a letter confirming this. Lauben

has never denied what he told me."

-

- Lauben later told the BBC that he was "mistaken,"

but the likelihood of a mistake is slight since he was a responsible officer

on the ground and saw both the camps and the reports.

-

- The difference between MacDonogh's and Bacque's treatment

of the subject of German prisoners of war in American hands is apparent

when we compare the attention each gives to the cutting off of food. MacDonogh

reports in one sentence that "any attempt to feed the prisoners by

the German civilian population was punishable by death." This is astounding

in itself and certainly deserves explication. Bacque tells us considerably

more: "General Eisenhower sent out an 'urgent courier' throughout

the huge area that he commanded, making it a crime punishable by death

for German civilians to feed prisoners. It was even a death-penalty crime

to gather food together in one place to take it to prisoners." He

says "the order was sent in German to the provincial governments,

ordering them to distribute it immediately to local governments.

-

- Copies of the orders were discovered recently in several

villages near the RhineS." On pages 42-3 of Crimes and Mercies, Bacque

publishes a German and an English copy of a letter dated May 9, 1945, by

which district officials were notified of the prohibition.

-

- Bacque provides evidence such as that of Professor Martin

Brech of Mahopac, NY, who was a guard at the U.S. camp at Aldernach in

Germany. Brech said that "he fed some loaves of bread through the

wire, and was told by his superior officer, 'Don't feed them. It is our

policy that these men not be fed.'" "Later, at night, Brech sneaked

some more food into the camp, and the officer told him, 'If you do that

again, you'll be shot.'"

-

- Thus, we find in Bacque a much sharper description and

attribution of responsibility than we do in MacDonogh. In light of the

immense detail given in MacDonogh's book, this would be forgivable were

it not for his attempt to blot out the work of a major scholar who has

studied the subject exhaustively.

-

- A similar cutting-short diminishes a reader's comprehension

of other important subjects, which MacDonogh touches on so briefly that

the reader is hardly able to form a full mental picture. For example, MacDonogh

tells how in the execution of Joachim von Ribbentrop at Nuremberg "the

hangman botched the execution and the rope throttled the former foreign

minister for twenty minutes before he expired." In his book Nuremberg:

The Last Battle, historian David Irving tells considerably more, including

the fact that the gallows had been designed in a way that allowed the trapdoor

to swing back and smash "every bone" in the faces of Keitel,

Jodl and Frick. He says that Goering's body (after Goering had committed

suicide by taking poison) "was dragged into the execution chamberS

[where] the army doctors [made] frantic attempts to revive him so that

he could be hanged."

-

- There are a number of places at which MacDonogh half-tells

about something important, only to leave it incomplete. We've already noted

his mention of "30,000-40,000 prisoners sitting in the courtyard [at

the Pioneers' Barracks in Worms]S With no protection against the rain they

froze." We are left to guess the consequences of their freezing. At

another place, he reports that "the Americans maintained camps for

up to 1.5 millionS Nazis or members of the SS." That is his only mention

of those camps, which one might suppose were even more punitive than the

others. Was MacDonogh too overloaded with other detail to pursue such matters

further? Did he deliberately refrain from exploring certain things? Or

was the failure due a scatter-gun recital of fragmentary details?

-

- A reader will need to assess the degree to which After

the Reich is a work of scholarship as distinguished from a narrative for

popular reading. MacDonogh includes many pages of endnotes, citing a large

number of sources. Very occasionally, he speaks critically of a given source.

But for the most part he accepts whatever a given source has to tell. The

book would profit greatly from a bibliographical essay in which he would

evaluate the principal sources, sharing with the reader a careful analysis

of the evidentiary basis for his narrative.

-

- An example of where a critical evaluation is essential

comes with his reference, say, to Ilse Koch's "lampshades and trophies

made from human skin and organs," which MacDonogh says the psychologist

Saul Padover claims to have been shown. We need to know what MacDonogh

would conclude if MacDonogh were to consider the counter-evidence that

calls the lampshade collection a "legend."

-

- The same holds true for MacDonogh's many citations to

Raul Hilberg's The Destruction of the European Jews. There is a vast scholarly

literature questioning every aspect of the Holocaust. One would never know

that that literature exists from reading MacDonogh, who either doesn't

know of it or finds it prudent, as so many do, not to mention it.

-

- Notwithstanding the book's limitations, After the Reich

accomplishes much when it provides another link in the chain of disclosures

that, over time, are providing conscientious readers with a more complete

understanding of modern history.

-

- The fact that, at the time of the events and for so many

decades thereafter, enormities of the greatest importance have been scrubbed

clean by propaganda suggests implications far beyond the events themselves.

The British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli observed that "all great

events have been distorted, most of the important causes concealed,"

and went on to say that "If the history of England is ever written

by one who has the knowledge and the courage, the world would be astonished."[15]

The implications suggest profound questions, which we would be remiss not

to mention:

-

|